Humans and art are inseparable. Thanks to the discoveries of cave paintings around the globe from France to Indonesia, dating back more than 40,000 years ago, we now have a better understanding that the urge for Homo sapiens to express what their senses perceive through drawings is very much in our DNA. Although we might never know the real reason for our ancestors to paint cavern walls with images of animals, over millennia the arts have evolved and branched out into a wide array of forms, from sculptures to architecture and mosaics. The latter, whose earliest known examples were created during the third millennium BC in Mesopotamia, were what drew me and James to the city of Madaba in Jordan.

Situated 30 kilometers to the southwest of Amman on the way to the Dead Sea, Madaba is a small city that receives a huge number of foreign visitors due to its historic sites, just like Jerash with its Roman ruins. Prior to the trip to Jordan I knew I had to include Madaba in the places I should visit in the country due to its mosaics, but little did I know that they would blow me away. On our third day in Amman, our driver who would take us to Madaba arrived on time – the punctuality of drivers here was one of the things I appreciated the most throughout our stay in Jordan. A few minutes later we were already navigating the busy streets of downtown Amman, taking a right turn near the Jordan Museum before heading onto the highway that connects the capital with the airport and cities in the south.

About half an hour after leaving Amman, we arrived at St George’s Church in the center of Madaba. In 1884, when the local Greek Orthodox population prepared this plot of land for their new church, they unearthed a piece of art that had long been forgotten. It would later be counted among the most important maps of the Holy Land ever produced, as it depicted Jerusalem, Bethlehem, the Dead Sea, the Jordan River, Jericho and other biblical places as they appeared in 560 AD. What people can still see today of the Madaba Map represents only a fraction of its original size.

I entered the church’s leafy grounds, we were met with large groups of tourists, probably on a pilgrimage around places in the Holy Land. The church was rather small, and to see that many people cramped into its nave with some of them talking really loudly was rather unpleasant. We waited, and ten minutes later the crowd had mostly dissipated, returning a sense of peace and tranquility to this place of worship. The Madaba Map sits right at the center of the nave, cordoned off by stanchions and a retractable belt barrier to avoid accidental damage to this ancient piece of art.

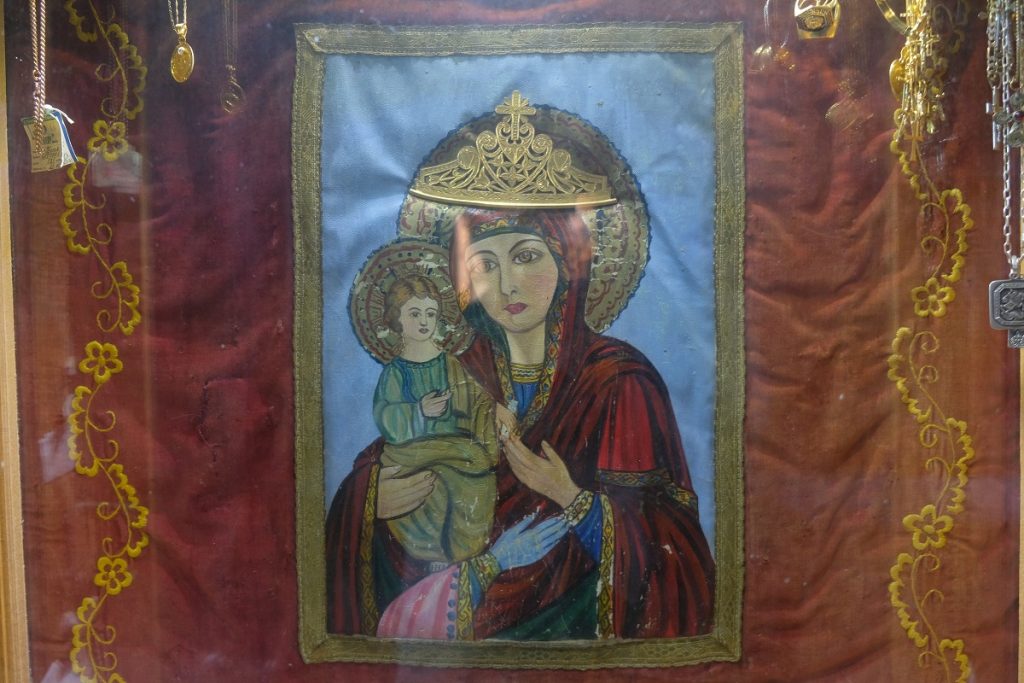

While it was fascinating to see an old map of places that are now scattered across countries and occupied territories that are often at odds with each other, another artwork stored in the crypt was equally, if not more, intriguing. A painting of a three-handed Virgin Mary carrying baby Jesus would certainly pique the interest of viewers. It is said that the tradition of this depiction of the Virgin Mary started in the eighth century AD when Emperor Leo III of the Byzantine Empire prohibited the veneration of icons. A writer known as John of Damascus criticized this decision through his writings in several publications, essentially attacking the emperor through words. Leo III then forged documents and sent them to the Damascus-based Umayyad caliph (probably Caliph Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik) accusing the writer of plotting an attack on the Muslim ruler. Unfortunately for John, the caliph bought the emperor’s story and ordered the writer’s hand to be cut off. Following this event, he fervently prayed in front of the icon of the Virgin, and miraculously his severed hand was restored. Grateful for this healing, he added a silver hand to this icon, and since then such a depiction of the Virgin Mary has been known as Tricherousa, or ‘Three-handed’.

We left the church, which by now was much calmer than when we first arrived, and walked a short distance to the Burnt Palace, a late sixth-century/early seventh-century residence of a local priest. When it was rediscovered in 1905, the mosaic tiles that once embellished the floor of the building were completely covered by a thick layer of ash and charcoal, pointing to a fire in the past that had destroyed the structure. Such mosaics were in fact the norm in ancient Madaba, a thriving urban center during the Byzantine period, which gave it the moniker the ‘Mosaic Capital of the Levant’. Only Antioch (near modern-day Antakya in Turkey) rivaled the quality and the quantity of the mosaics being produced here. Not many visitors were at the Burnt Palace when we wandered around the compact archaeological park, giving us plenty of space to contemplate the bucolic scenes portrayed on the tiles in faded colors. Looking up, I caught sight of the imposing minarets and yellow domes of King Hussein Mosque set against a cloudless blue sky.

Just a short walk down the street, lined with all sorts of souvenir shops spilling out onto the sidewalk, we came upon the entrance of the Madaba Archaeological Park (often dubbed Part I, for Part II in fact covers the Burnt Palace and its immediate surroundings). After having our Jordan Pass printouts stamped by an elderly man, off we went to explore this rather deserted place. Opened in 1990, Part I of the archaeological park houses Byzantine mosaics retrieved from churches around Madaba, arranged around a corridor that leads to a large roofed enclosure with metal stairs and a narrow pathway for visitors. I went up, followed the pathway and the most spectacular set of mosaic tiles suddenly appeared before my eyes.

A rectangular mosaic was laid out with the utmost precision beneath my feet. At the center lay a medallion with Greek inscriptions inside an Islamic octagonal star. Around it, a procession of circular, floral and crisscrossing patterns overlapped each other in an almost arabesque manner. At one end, a tabula ansata (a tablet or tablet-like shape with dovetail handles or edges) also bore a Greek inscription. These juxtaposed styles of art are apparently a result of the continuous use of the structure despite the region changing hands from the Byzantine Empire to a series of Islamic dynasties. I was, in fact, standing above what was once the floor of the Church of the Virgin Mary which was restored by the Muslim rulers of the Umayyad and Abbasid caliphates, indicating a harmonious coexistence of followers of the two religions in Madaba at that time. The church was built upon the foundations of a sixth-century mansion, known today as the Hippolytus Hall, which itself was constructed atop a circular Roman temple.

At the end of the pathway, the incredibly well-preserved mosaics of the mansion came into view, depicting a number of animals and the protagonists of the Greek tragedy ‘Hippolytus’ by Euripides. Its titular character, the illegitimate son of the King of Athens, vows to live chastely and therefore revers Artemis instead of Aphrodite. This enrages the latter goddess, and she makes the man’s stepmother fall in love with him, which results in her committing suicide. The king in turn gets angry and curses his son with banishment and death, before Artemis eventually intervenes on the dying Hippolytus’ behalf. At the four corners of the mosaic panel are images of Tyche – the Greek goddess who governed the fortune and prosperity of a city – in different styles personifying the seasons. Meanwhile, at the top left of the panel, three depictions of the same goddess symbolize the three cities of Rome, Gregoria and Madaba. Scholars have different opinions about which Rome it refers to – the one in Italy or Constantinople, the center of the Eastern Roman Empire. However, even more bewildering is Gregoria as no one has been able to identify any city in that period with this name.

Strangely, the impressive mosaics of this archaeological park in Madaba only attracted a handful of visitors – less than a dozen, to be precise, during the 50 minutes we spent here. While the Madaba Map was certainly interesting, it was the mosaics of the Hippolytus Hall and the Church of the Virgin Mary right on top that became the highlight of our visit, something we didn’t expect at all as most references we had read prior to coming only gave these mosaics a brief mention compared to the extensive and elaborate descriptions of the mosaic map of the Holy Land. Astonished and satisfied, we walked back to St George’s Church to find our driver waiting across the street, where we began. Through the car window, I saw other groups of tourists flocking into the church. I was quietly hoping some of them would make their way to the Burnt Palace and the Church of Virgin Mary, for they would certainly be blown away by the magnificence of the mosaics there.