Visiting a new country with a completely different culture and where the people speak a language you don’t understand can undoubtedly be daunting. But everyone has their own way of getting their bearings. And for James and I, we usually visit the national/most important museum of a country (usually in the capital or biggest city) to get a better understanding not only of the history of the sites we will see throughout the trip, but also the nation itself. This was exactly what we did the day after we arrived in Seoul, as well as in Beirut before we ventured deeper into the mountainous region of Lebanon, and in Amman prior to leaving the capital for the Jordanian desert. Language-wise, Mexico was easier for James than it was for me. However, culturally the Latin American country is so different from our home in Asia.

James, with his Hong Kong upbringing, can point out the cultural similarities among East Asian countries. And I, who grew up reading and listening to stories inspired by Hindu epics, can see traces of Hinduism in local customs and traditions across Southeast Asia. Along with trade activities between kingdoms and empires in Europe, the Middle East, and Asia since antiquity, there have also been cultural exchanges among these regions for millennia. While some influences were palpable, others were more subtle. Greco-Roman facial features on Buddhist statues found in Pakistan and Afghanistan, Chinese-inspired porcelain made at workshops across Europe, and Islamic architectural elements incorporated into mosques that resemble ancient Hindu temples in Java are only a few examples of such exchanges.

However, on the other side of the globe, separated from Eurasia and Africa by vast oceans, was Mesoamerica. It was a cultural region where ancient civilizations developed their own beliefs, technology, systems of governance, and architectural styles, among other things, independently from the rest of the world, thanks to its geographical isolation. All of this created unique cultures, reflected in everything from food to monumental structures, that were the main reason for James and I to put this part of the world among the places we most wanted to visit.

Prior to our trip to Mexico almost two months ago, we had read great reviews about the Museo Nacional de Antropología (MNA) in Mexico City. The modern institution’s history, however, can be traced back to the 18th century when the country was still part of New Spain. An Italian-born historian and ethnographer by the name of Lorenzo Boturini amassed a collection of pre-Columbian artifacts from various parts of the Spanish-controlled territory, copied inscriptions written by ancient Mesoamerican peoples, and made drawings of the ruins and sculptures he stumbled upon throughout his explorations. Following the independence of Mexico from Spain in 1821, Boturini’s collection was transferred to different state institutions, before in 1940 its custody was finally entrusted to the then newly-formed Museo Nacional de Antropología.

In the early 1960s, three Mexican architects were tasked with designing a new compound for the museum. And in 1964, the current premises of the institution were inaugurated. On our second day in Mexico City, under bright blue skies and blooming jacarandas, we joined other visitors lining up to get inside the modernist structure. From the outside, the museum looked rather austere. But once we went past the first building and walked into the courtyard, a giant umbrella (“el paraguas” in Spanish) with water running down along its edges welcomed us and other visitors. Apart from the artifacts themselves, this unique structural and artistic element of the compound must be among the most photographed objects at the museum. After marveling at it, we then had to decide where to start, and we opted to go to the right where the hall of Teotihuacan awaited.

Teotihuacan and the Toltecs

The pyramids of the ancient city of Teotihuacan that are situated to the northeast of Mexico City were firmly on our list of places we wanted to see on this trip. That’s why we knew we had to check out a section of the museum dedicated to the civilization that built those imposing monuments.

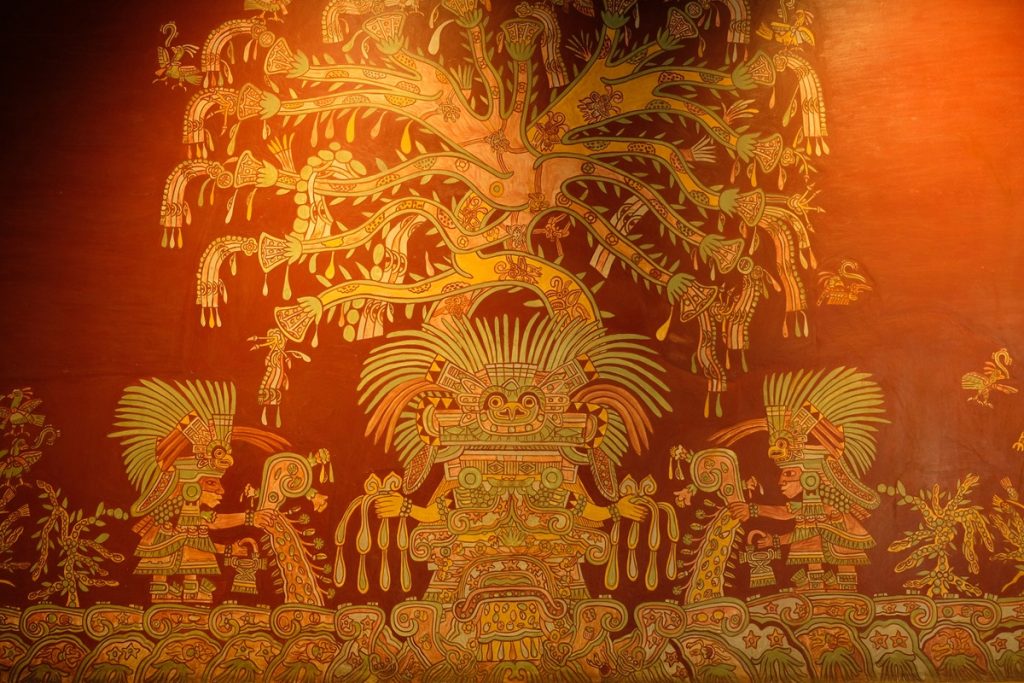

While the Pyramid of the Sun, the Pyramid of the Moon, and the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent are among the most impressive ancient structures in Mexico today – almost 2,000 years since they were constructed – relatively little is known about the society that erected them due to the lack of written records about them. What archaeologists managed to salvage from the ruins, however, were then relocated to the MNA as their permanent home. Some of the artistic creations left by the same people were then reproduced at the museum so that present-day visitors can get an idea of how festive and colorful the walls of Teotihuacan were during the heyday of this city.

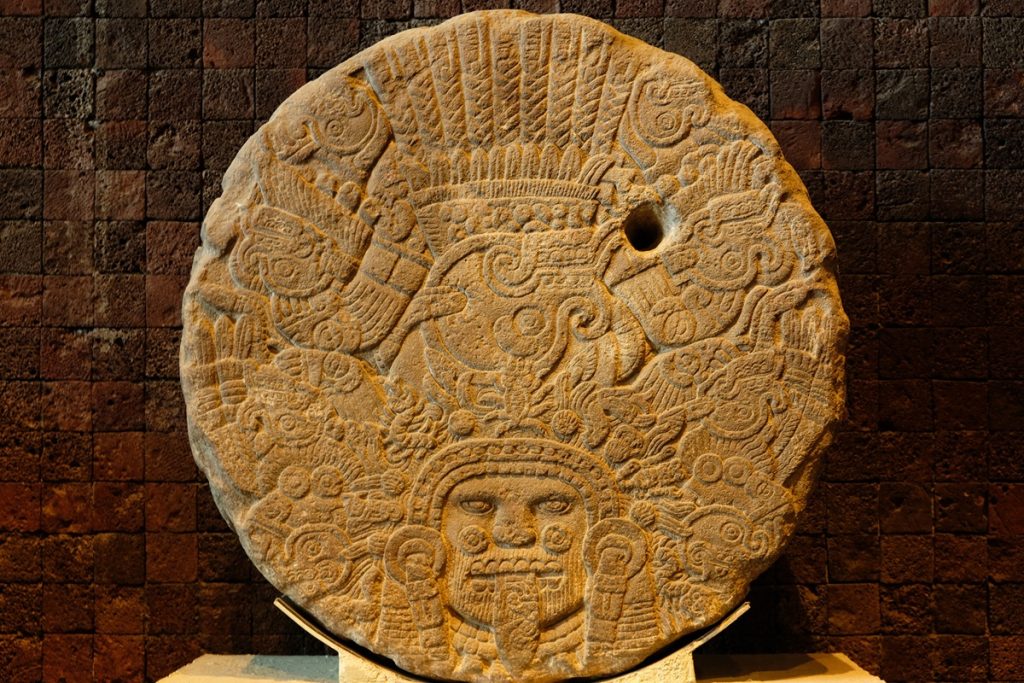

As we entered the hall, the Disk of Mictlantecutli beckoned visitors to come closer and explore this section further. Although the artifact was discovered in Teotihuacan, it is unclear whether it was created by the residents of Teotihuacan or by the Aztecs, a Nahuatl-speaking people who would dominate this region centuries later. We followed the path to the right, and moments later as I walked to the main exhibition hall, I was wonderstruck with my mouth agape and goosebumps all over my arms. Standing before me was a giant structure that was a reproduction of a portion of the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent. This was how the structure must have looked like almost two millennia ago when it was still painted in brilliant colors.

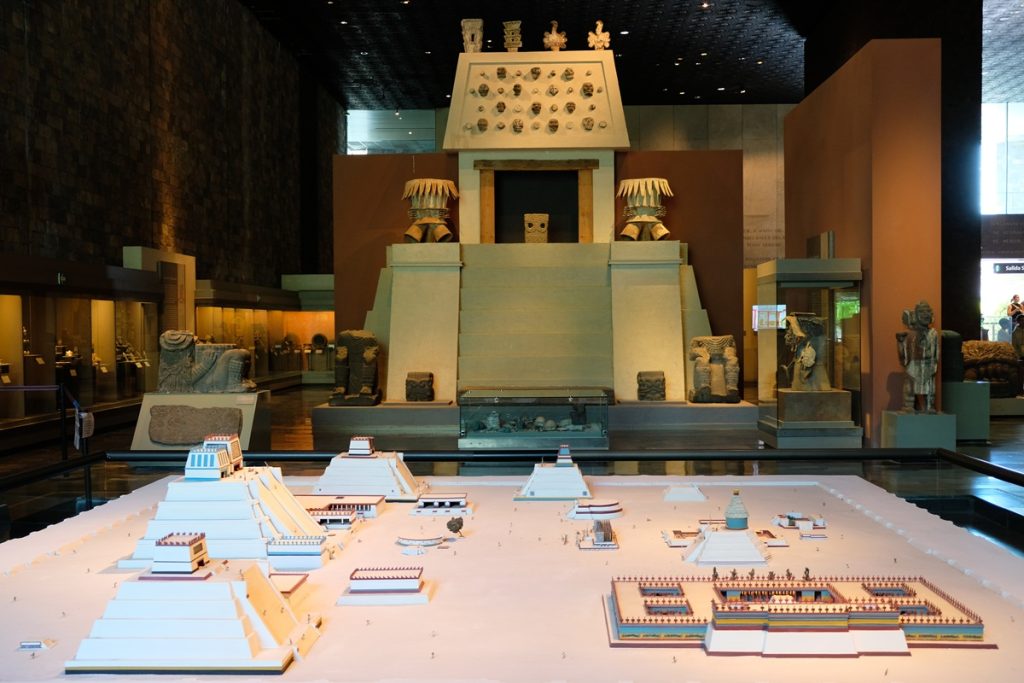

Elsewhere in the gallery, numerous artifacts unearthed from Teotihuacan were displayed to shed light on this rather mysterious culture. One giant statue of Chalchiuhtlicue, in particular, caught my attention as it was carved out of andesite, a type of volcanic rock that is also abundant in Java, making it the preferred material for building many of the tropical island’s most impressive ancient Hindu-Buddhist temples. Another thing I found so interesting about the MNA was the fact that in addition to indoor halls, each section of the main exhibition halls has an outdoor area that is cleverly used to give visitors more context about what they are seeing. In the Teotihuacan section, for example, a model of the great ancient city complete with the pyramids sits directly outside the main hall to give an idea of its scale.

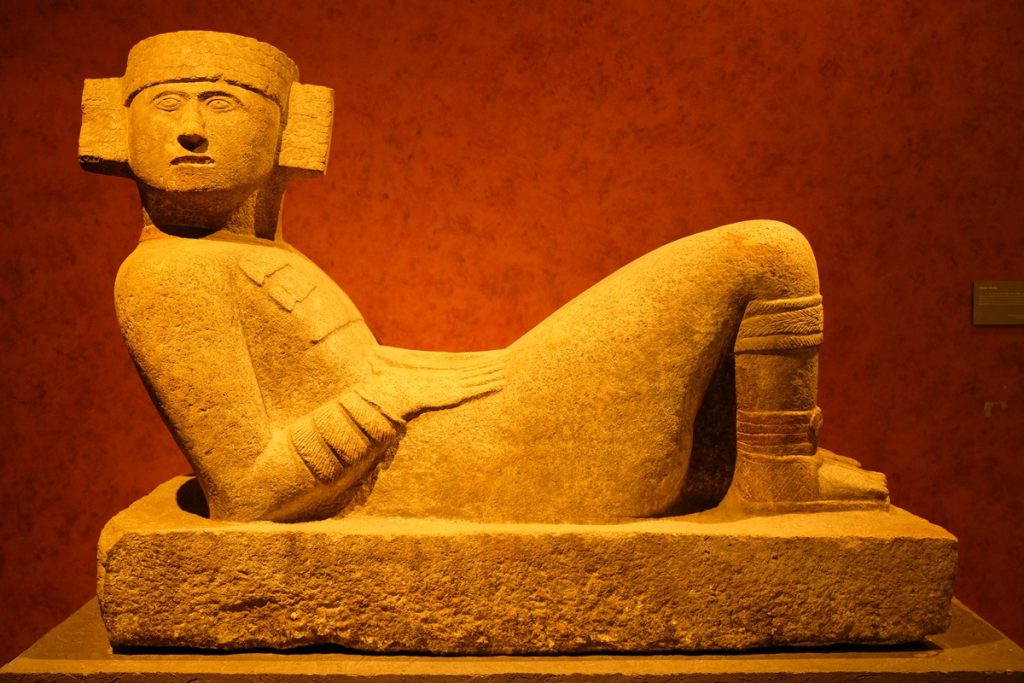

Walking further to the adjacent hall brought us to the section on the Toltecs with their iconic giant Atlantean pillars. We didn’t spend too much time in this area since we weren’t planning to see Tula or any other regions of Mexico with significant Toltec-era ruins. However, it was neat to get a closer look at the vestiges of another ancient culture of this country that one day I hope I will get the chance to see at their original locations.

Left: A figure of Cocijo, the Zapotec god of rain, thunder, and lightning; Right: A monolith of Chalchiuhtlicue, the Aztec goddess of water, seas, oceans, rivers, streams, and baptism. Both are non-Teotihuacan cultural elements found in the ancient city

The Maya

Despite their lack of a writing system, the people of Teotihuacan were very successful in expanding their influence to far corners of Mesoamerica, including the realms of the Maya people in what is now southeastern Mexico. After the decline of Teotihuacan, the Maya civilizations began to flourish, a period that witnessed a construction boom in Mayan city-states over the centuries. Seeing the great monuments the ancient Maya left behind were the very reason James and I decided to travel halfway across the globe to Mexico.

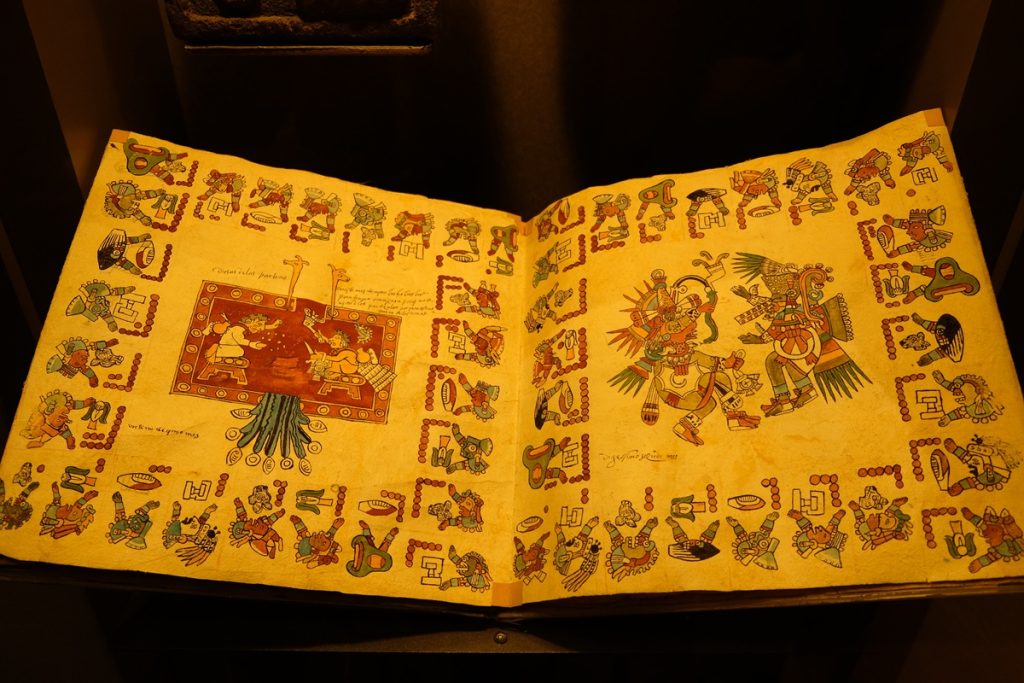

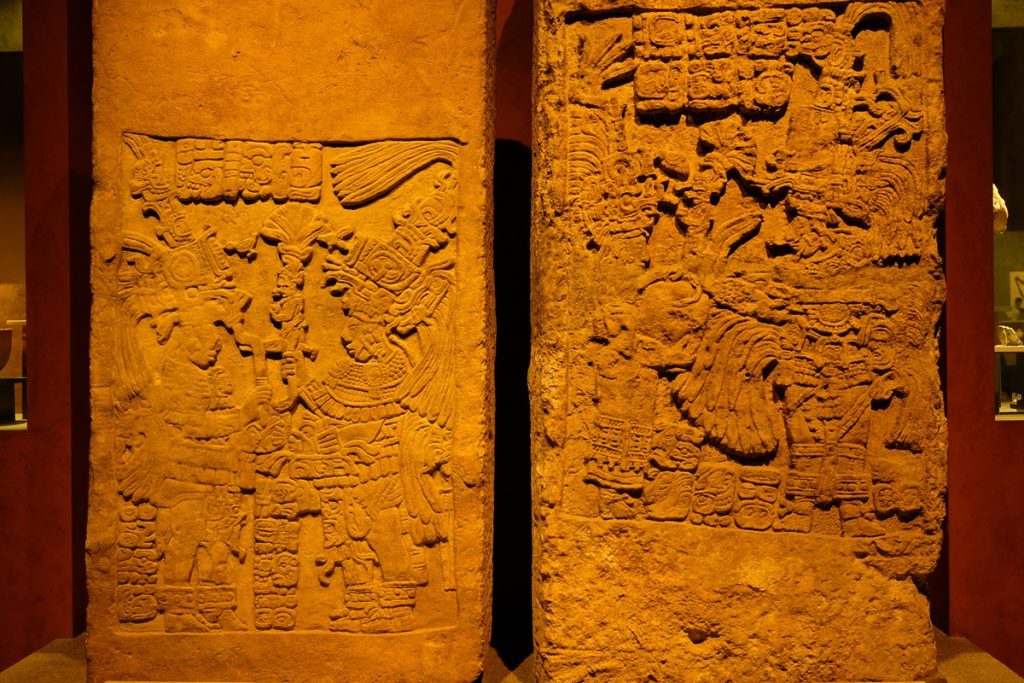

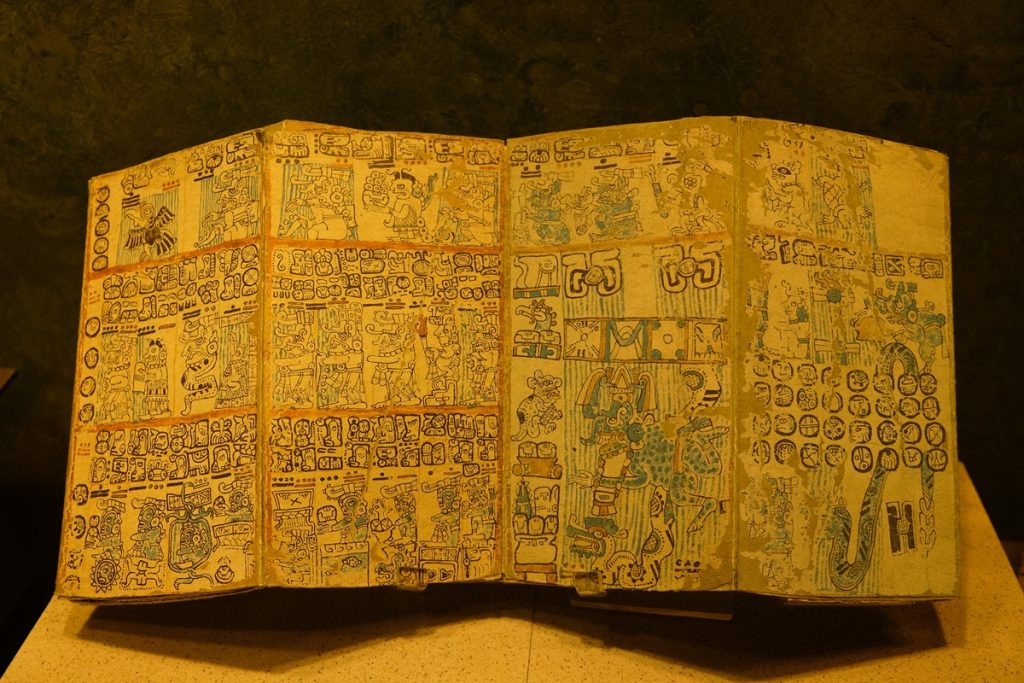

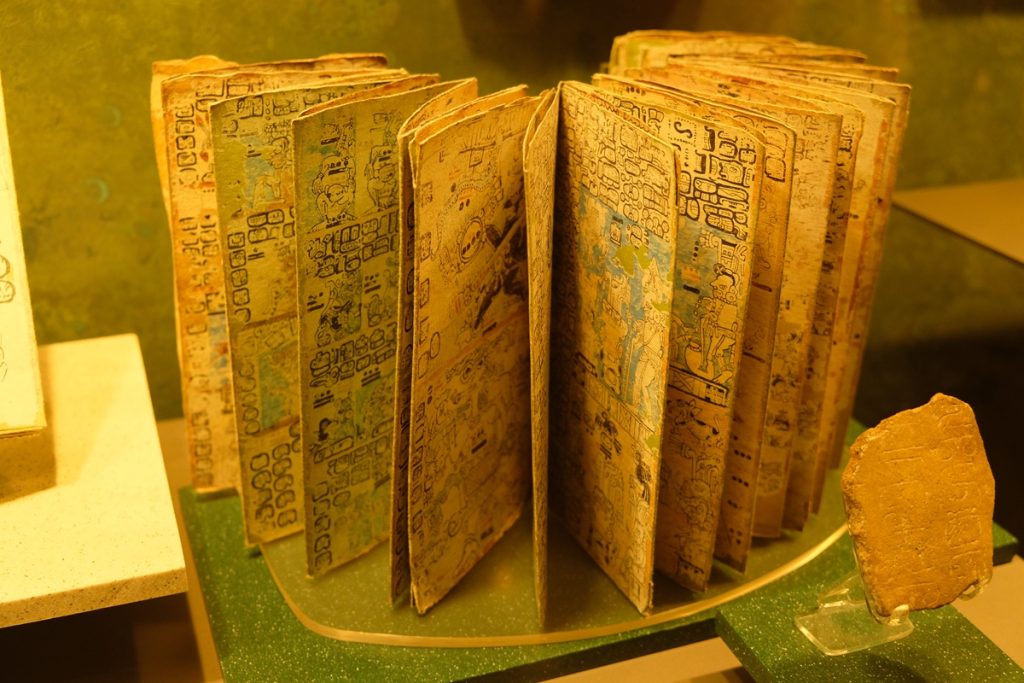

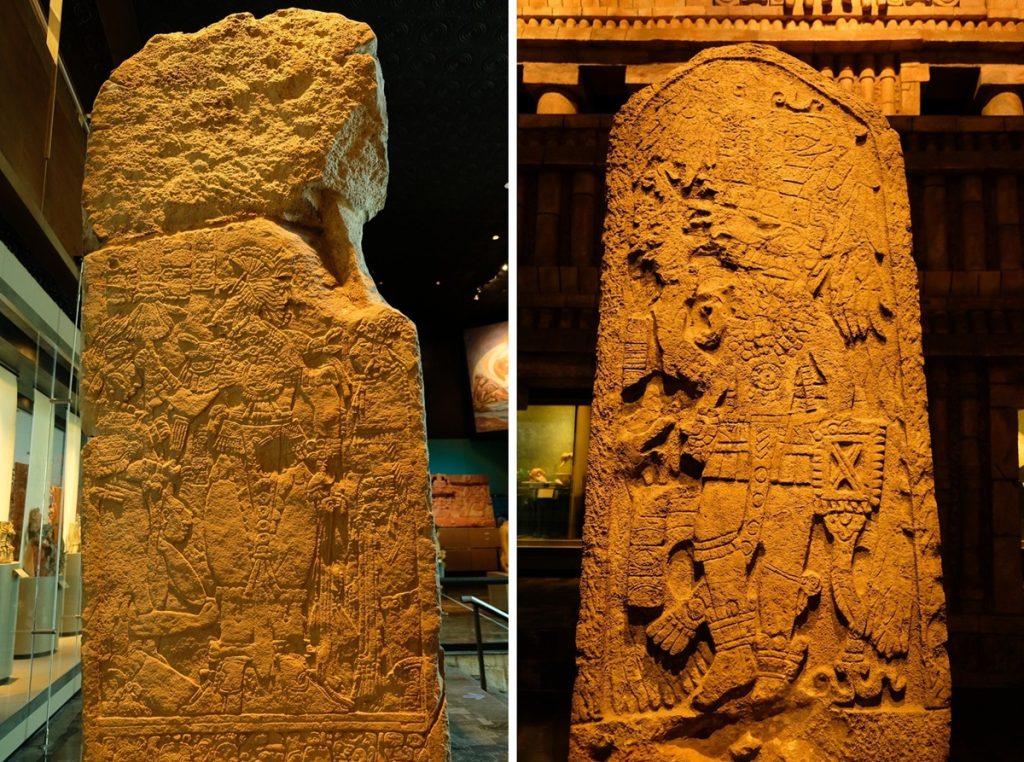

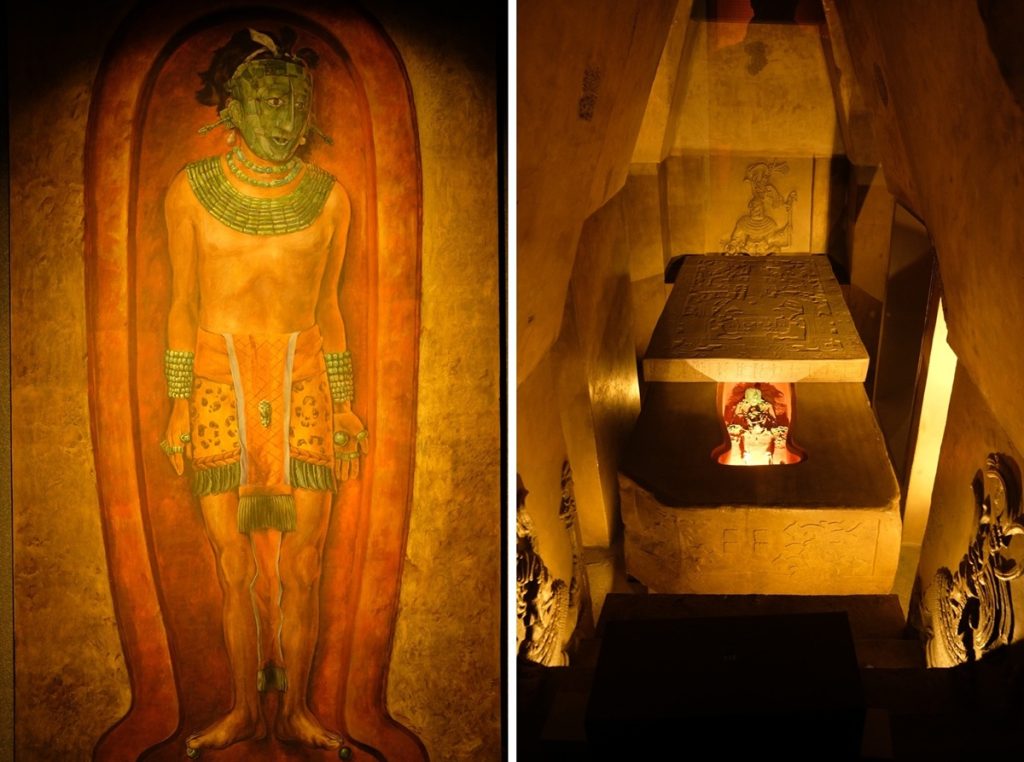

From Mexico City, we would travel to Palenque in Chiapas then Mérida in Yucatán to visit among the most famous ruins built by the Maya civilization. That’s why we knew we should also check out the Maya section of the museum to gain a better understanding of this unique culture before seeing the actual ancient sites. Unlike Teotihuacan (or the Aztecs centuries later), the Maya peoples of Mesoamerica were never united under one central government. However, the different Maya city-states had one thing in common: they employed among the finest sculptors in Mesoamerica to carve out exceptionally detailed inscriptions (glyphs) – replete with iconography of Maya deities – as well as beautiful and often whimsical ornamental elements for their great palaces and temples. It was incredibly exciting to see some of the best works of art created by the ancient Maya at the museum. But don’t skip the underground gallery as it is now home to the original jade mask of Pakal the Great, the ruler of Palenque for 68 years, making him one of the longest-reigning monarchs the world has ever seen.

While the Teotihuacan section has an impressive replica of parts the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent, the Maya section has an equally spectacular reproduction of the Northern Palace of Sayil – a lesser-known archaeological site we also visited later on this trip. Meanwhile, the outdoor area of the gallery had replicas of a few Maya structures from remote sites that are rather difficult to reach, including Bonampak whose centuries-old murals provide a glimpse into the colorful world of the ancient Maya peoples.

The Mexica (Part of the Aztec Empire)

Situated at the center of the museum compound is what seemed to be the most popular gallery among visitors. Showcasing the archaeological finds discovered in the ruins of Tenochtitlan, the awe-inspiring capital of the Mexica (Nahuatl-speaking people who held dominance over the Aztec Empire) upon which Mexico City was built, this part of the museum is where the Aztec sun stone is located. This artifact must be among the most photographed items from the museum’s collection, and I could see why. Placed on a pedestal above a center stage, its size and awe-inspiring details will definitely catch everyone’s attention.

The Mexica lived in a period archaeologists defined as the Late Postclassic, a chapter in the history of Mesoamerica that saw the rise of the Aztec Empire and the decline of the Maya civilization, which ended with the arrival of the Spanish. Continuing the long-standing tradition carried out by indigenous Mesoamerican peoples of creating intricately-decorated buildings and objects, the Mexica produced among the most ornate objects ever unearthed in Mexico. However, they also ruled during a period that also saw the rise of the predominance of militarism in all aspects of life. Their main gods were the patrons of military conquests, and the most important ceremonies revolved around the capture of prisoners and human sacrifice. This, unfortunately, is what often shapes the image of the ancient Mesoamerican peoples in popular culture today, eclipsing the many achievements they attained in different aspects of life, from science to architecture.

The stone carvings the Mexica made were undeniably incredible. But what is more mind-blowing for me is the fact that they built their capital – Tenochtitlan – on a small island in the middle of a lake. It has been mostly drained since then to allow the construction of more buildings for the capital of New Spain: Mexico City. However, centuries later, this idea is proving to be not so brilliant as it might have sounded at first. Now, the modern capital of Mexico is sinking fast, and many of its old buildings are visibly leaning. But that’s for another story.

After around three hours exploring the four galleries of the Museo Nacional de Antropología, we realized that it’s simply impossible for us to see all the parts of the museum in one visit. We decided to skip the sections on the cultures of Oaxaca (including the Zapotecs), the Gulf of Mexico (this is where you can see the iconic giant heads created by the Olmecs), and the rest since we were not visiting any of those regions on this trip. However, when we return to Mexico one day to explore more ancient sites in this fascinating country, we know we have to go back to this awe-inspiring museum.

Left: A tall statue of Coatlicue, the goddess who gave birth to the moon, stars, and the god of the sun and war; Right: A rare depiction of Ehecatl, the god that produced the wind