I don’t remember exactly how it started, but apart from my penchant for ancient sites, now I also have a soft spot for urban renewal projects. These are initiatives and programs aimed at revitalizing dilapidated parts of a city to make them more lively, more accessible, and healthier – generally turning them into better versions of themselves. Different cities have their own way of achieving this goal, but it often involves preserving heritage buildings and transforming them into spaces that are relevant to the current needs of the local community. Also known as adaptive reuse, this is a trend that doesn’t seem to be abating anytime soon, and I genuinely think it is a good thing.

From a half-empty traditional market that is partially turned into a hub for independent small-scale retailers to a former post office that is better known today for hosting creative events, Jakarta joins a slew of urban areas in the region that embrace adaptive reuse in earnest. However, there is one city close to my heart that has been doing this exceptionally well: Hong Kong. Before the pandemic, I visited two particularly interesting sites there that were excellent examples of urban renewal: the former police station of Tai Kwun and the old warehouses of a textile company collectively called The Mills. And when Hong Kong finally reopened its borders to the world, I immediately booked my flights and returned to this endlessly fascinating city to check out similar projects it has to offer.

Despite its location close to the heart of the financial district on Hong Kong Island, it was only in December 2023 that I finally set foot in the Asia Society Hong Kong Center, one of the outposts of the namesake New York City-based nonprofit organization that was initiated by the Rockefeller family in 1956. Built in the 19th century to store explosives for the British Army, the compound was given a new lease on life in 2012 following a conservation and restoration effort that saw not only the refurbishment of the old structures, but also the addition of elevated walkways that crisscross the hillslopes on which the original buildings were constructed.

Once James and I stepped inside the compound, I couldn’t help but feel peaceful, thanks to the dense foliage covering the hills and the soothing sound of water running down the concrete drainage channel underneath. During our visit, a temporary exhibition was held at one of the old buildings, showcasing some of the best works of Pang Jiun, a prolific Taiwanese painter hailed as a master of “Eastern Expressionism”. Deeper within the compound were beautifully-restored former explosives magazines, a laboratory, cannons, and munition tracks from the British period. And if one gets hunger pangs while exploring this cultural and intellectual center, a rather fancy-looking restaurant aptly named Ammo can be found two floors beneath the reception level. We didn’t dine there though.

Across Victoria Harbour in Kowloon’s Mong Kok neighborhood, the Urban Renewal Authority (URA), a body responsible for accelerating urban redevelopment in Hong Kong, had carried out an equally interesting project. The facades of ten historic buildings constructed in the 1920s between No. 600 and 626 Shanghai Street were preserved and revitalized by the URA following their decline decades after their heyday as a commercial hub. Now collectively called 618 Shanghai Street, this cluster of old shophouses has been transformed into spaces filled with attractive independent retailers, from vintage stores selling household items that were popular across Asia during the time when Hong Kong was a manufacturing hub to a Japanese-inspired wabi-sabi ceramics studio.

Beautiful murals evoking the past adorned some corners of the compound, including a wall depicting the now-demolished Bird Street, once famous for the many stalls specializing in pet birds. But not everything in this mall is about nostalgia of the good old days. At a rooftop restaurant called Poach, we were joined by James’ cousin E for an al fresco lunch of grilled eel, poached egg, and pickled vegetables. While the food was good, E noticed the rather surly server with James quickly adding that Hong Kongers should learn from Southeast Asians when it comes to hospitality.

Back on Hong Kong Island, a bigger urban renewal project had been implemented by the URA and was reopened to the public in 2021. Central Market traces its history back to the 19th century when it began as a wet market – the first in the former British colony. In 1937, the old building was demolished and replaced with a new structure designed in the Bauhaus and Streamline Moderne architectural styles. This incarnation of the market was inaugurated in 1939 and operated for decades. However, the 1990s saw the market’s fortunes declining as customer behavior began to shift. Parts of the market were torn down to make way for the construction of the Central–Mid-Levels escalator, the world’s longest outdoor covered escalator system – which itself is very impressive. By 2003, the market was largely abandoned with only a few shops that remained open. In 2017, the URA finally stepped in and a four-year preservation project commenced.

Compared to the compact mall we visited earlier in Mong Kok, Central Market is a lot bigger and, in some ways, flashier. It also benefits from its central location. When we went, there was a Christmas-themed children’s piano competition in the atrium with curious onlookers watching the performances from the terraces above it. My favorite part of this place, however, was the beautifully-designed bright-looking vintage signage as it gave the redeveloped market a touch of sophistication.

Further to the east of Hong Kong Island in North Point, there was yet another adaptive reuse project that proved to be a favorite place for hanging out among the locals. In 1908, the Royal Hong Kong Yacht Club built their headquarters and clubhouse on this location which used to be by the harbor. However, subsequent land reclamation made this compound lose its prime waterfront location and pushed it further inland. After World War II, it was used by the Government Supplies Department until 1998 when the premises were rented out. This attracted a number of artists to lease the space and turn it into the Oil Street Artist Village. But a few years later, the government decided to evict the tenants and handed the management of the compound to the Antiquities and Monuments Office.

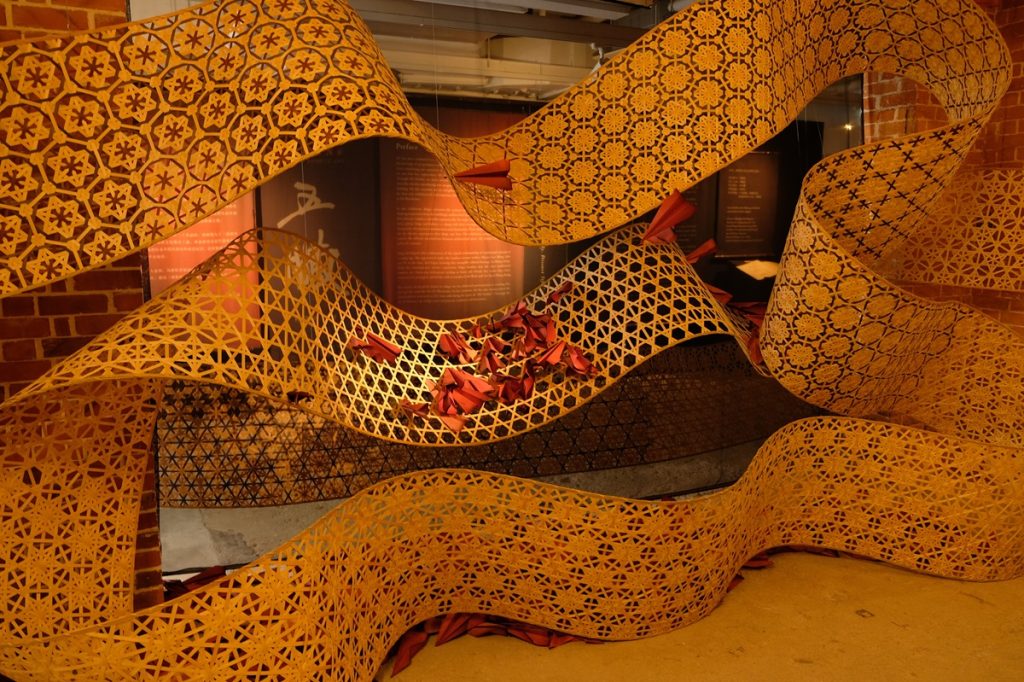

In 2007, the Hong Kong government assigned the Leisure and Cultural Services Department to redevelop the site, a project that would take six years to finish. It was then reopened as Oil Street Art Space (marketed as Oi!), an organization that promotes visual arts by providing a platform for the city’s aspiring talent to showcase their works, which are intended to spark discussions among the public. When we visited, there was a visually-intriguing exhibition by Inkgo Lam, a homegrown artist specializing in bamboo craftsmanship. Among her works on display were bamboo-inspired kinetic sculptures that drew parallels with how human organs work, figuratively speaking.

As I left the final of these four sites, each a brilliant case of inspiring urban renewal project, I couldn’t help but think of how far Hong Kong has come in the sense of conserving its architectural treasures. It appears that the city no longer favors razing old buildings to erect new ones. Now it sees great potential in preserving its decades- and centuries-old heritage structures and making them relevant today, which adds more charm to the city itself. I won’t be surprised if the next time I come the metropolis offers even more exciting urban renewal projects to explore and learn about.