The Spanish-built Afrosiyob high-speed train whisked us through a landscape that gradually changed from one filled with endless cotton fields at the peak of harvest season, to vast steppes, before eventually giving way to barren hills. We left the wonders of Samarkand behind and arrived in Bukhara, although one would be forgiven for having the impression that the latter – which was also part of the fabled Silk Road – looks rather unassuming. That’s because the station serving the high-speed rail line is in fact located in Kogon (also spelled Kagan), a satellite city some 15 kilometers to the southeast of the old town district of Bukhara.

Outside the train station, we were trying to look for a taxi driver and settled with one after realizing that there were not many of them as most people seemed to have arranged transport either with their hotels or travel agents, or through online apps. As expected, this would cost us more than it should. But with the limited options we had, we thought it was fine as long as he took us to our accommodation. Along the way, colorful banners emblazoned with the emblem of the 2024 FIFA Futsal World Cup, held in three cities in Uzbekistan, were spotted in some strategic corners of Bukhara. This was in fact the first FIFA tournament ever hosted by any Central Asian country, hence the palpable enthusiasm.

It didn’t take that long for us to arrive at the lodging, our home away from home for the next four nights and right outside the UNESCO World Heritage-listed historic center of Bukhara. The skies were gloriously blue, but since the early afternoon sun was still too strong for taking photos of the city’s centuries-old buildings, we decided to walk to a modest local joint not far from where we stayed to have lunch. Flaky warm somsas, delicious plov, and refreshing achik chuchuk salad not only sated our hunger, but they further opened our eyes and palates to the little-known wonder that is Uzbek cuisine – I will eventually write a blog post dedicated to the food we had throughout our trip to Uzbekistan. We left the place with full and happy stomachs. And as the sun was already lower in the western sky, we made our way to a part of the old town area closest to where we stayed: the Ark of Bukhara.

If you wonder why this ark in Bukhara does not resemble a chest or a large box, like the legendary Ark of the Covenant, that’s because the word to describe this particular structure was actually derived from arg, Persian for “citadel”. The 18th-century ceremonial entrance at the west side of the compound immediately caught my attention for its imposing architectural style. The ramp further accentuates the structure’s significance as it gives a dramatic experience to anyone walking on it to enter the ark. The undulating defensive walls which were aesthetically pleasing and strangely soothing to look at – not a quality I would typically attribute to fortresses – were another aspect of the compound I couldn’t take my eyes off.

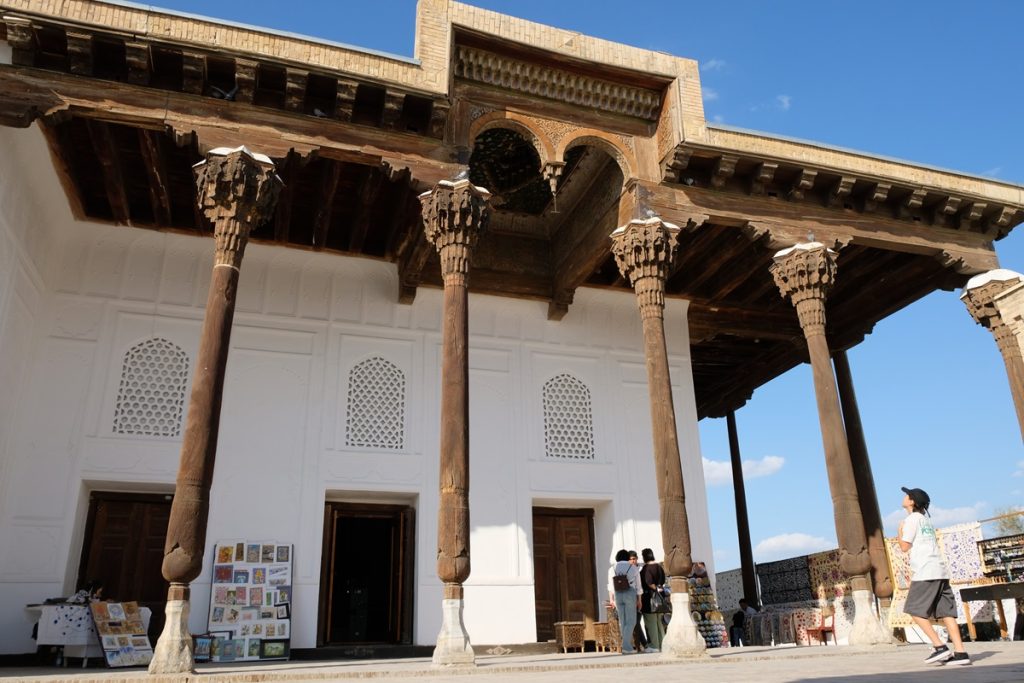

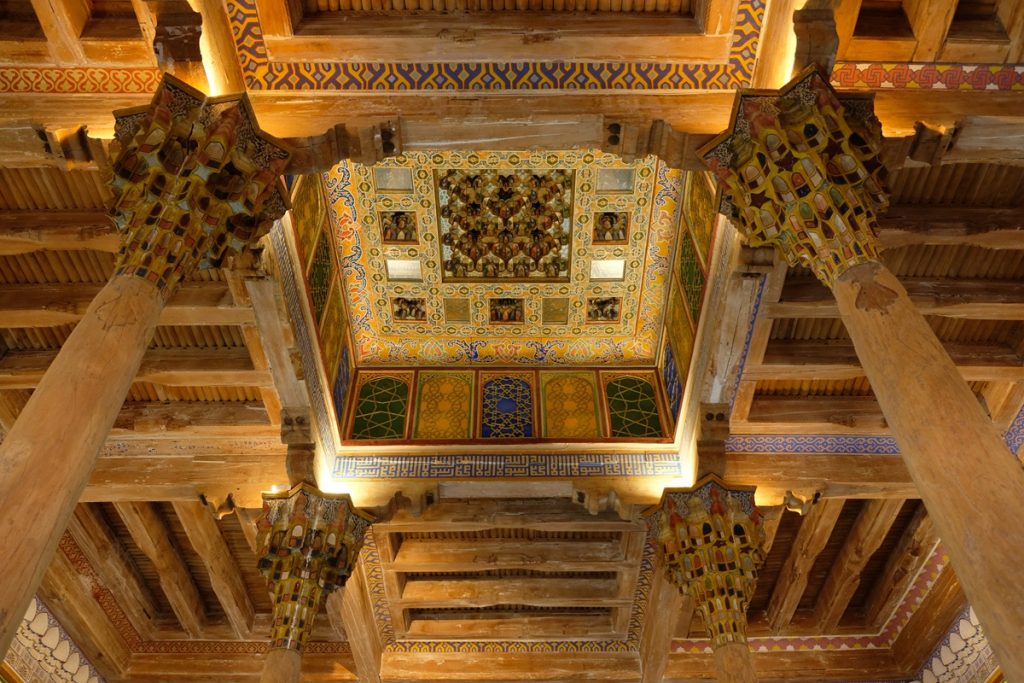

Soon, we walked through the impressive gate and entered the ark. At the end of the ramp was the small but beautiful Juma Mosque, which was also commissioned in the 18th century. The history of this citadel, however, goes back more than two millennia. It is unclear who first erected a structure at this very location, but over the course of centuries, multiple edifices were built and rebuilt on the exact spot. At one point, there was even a Zoroastrian temple standing inside the citadel, signifying the influence the ancient Persians had over Bukhara.

Due to the destruction suffered by early iterations of the ark, it is believed that at one point the ruler of Bukhara, after consulting his advisers, demanded the citadel to be rebuilt with the guidance of the stars, quite literally. Taking the Ursa Major constellation with its seven main stars (collectively known as the Big Dipper) as the inspiration, the compound was reconstructed with seven stone markers placed at seven corners of the structure. Following the conquest of the city by the Muslim army of the Umayyad caliphate in the eighth century, the vanquishers didn’t change much of the structures within the citadel, except for the replacement of the Zoroastrian temple with a mosque. But this was different from the Juma mosque I mentioned earlier. In fact, with a total area of a little less than 4 hectares, the Ark of Bukhara is only slightly smaller than the Vatican City – the world’s smallest country today. And just like the seat of the papacy, a multitude of buildings serving different purposes were once contained within the ark’s walls.

As kingdoms and empires rose and fell, control of Bukhara changed hands multiple times. In spite of this, the ark remained the center of power for whoever governed this important trading hub and its surrounding regions. In 1785, the Emirate of Bukhara was established, but most people would probably have never predicted that it would eventually become the last Muslim polity to ever rule this city. In 1868, the Russian Empire defeated the emirate and took a lot of its territories, including the city of Samarkand, while Bukhara itself became a Russian protectorate in 1873.

In 1911, a new emir, whose power was limited to internal affairs, ascended the throne of Bukhara. Being rather unpopular, the new ruler further alienated himself from his own people due to his conservative leanings, and this provided the impetus for reformists to remove him from power. The Bolshevik Revolution that swept across Russia only hardened the anti-monarchist elements in Bukharan society. And eventually, in 1920, after a continuous assault on the Ark of Bukhara by the Red Army, and an aerial bombing that severely destroyed parts of the citadel, the emir fled to Dushanbe, Tajikistan then Kabul, Afghanistan. This marked the end of the Emirate of Bukhara and the full absorption of its former territories into the Soviet Union.

Contrary to the fate of the once formidable USSR which collapsed in 1991, the Ark of Bukhara has seen waves of revival, especially since its inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage list in 1993. Today, the ark provides a good starting point to explore the ensemble of old buildings within the historic center of Bukhara, which was exactly what we did. After navigating the narrow alleys that weaved through the structures within the citadel, we arrived at the southeastern corner of the ramparts with a view of old Bukhara that evoked my imagination of the long-lost past when caravans were still a common sight in this bustling Silk Road hub. Meanwhile, the turquoise domes and the iconic Kalon (Kalyan) Minaret that stood proudly before our eyes not only exuded a deep sense of reverence; they were also silent witnesses to the vicissitudes of the Tajiks of Bukhara, a people whose struggle to adapt to the new realities around them is as intriguing and fascinating as the place itself. But that is a story for another day.