On our penultimate day in Samarkand, grey clouds persistently hung over the city. But we had anticipated this and decided that we would spend the day visiting the sites further away from the city center, on foot. I have mentioned this before, but we do love walking when exploring a new city. However, since none of us are familiar with the place, we always do a little research in advance on the route we should take and what to see (or avoid) along the way. This was exactly what we did in Samarkand. After marveling at the centuries-old architectural wonders commissioned by Timur and his grandson Ulugh Beg, we realized we should also check out the ruins of a 15th-century observatory which was the brainchild of the latter who established his capital as an important center of science and learning.

The problem is, what is known today as the Ulugh Beg Observatory is located around 5 kilometers uphill to the northeast of the Registan. So, we knew we had to devise a plan to make the excursion worthwhile by including other places of interest in the itinerary. But where should we begin? Thankfully, Maggie and Richard from Monkey’s Tale had written about some sites around Samarkand that piqued my curiosity. One particular mausoleum that is purported to be the final resting place of Doniyor (also known as Daniyar, Daniel or Daniil), a prophet/saint revered by Muslims, Christians, and Jews, is supposedly only a few minutes’ walk from the observatory. And thanks to Joanna Lumley’s Silk Road Adventure documentary series, I figured that visiting the Afrasiab Museum further down the hill on the way back to the city center is a must to better understand the Sogdians, an important ancient civilization that once ruled this region.

Under the grey skies, we hailed our only taxi for the day from right across the ever-impressive Registan. As usual, we memorized the Uzbek names of the places we wanted to see beforehand, just in case we would need to ask the locals for directions, or take a taxi. We learned that rasadxonasi means observatory, but luckily our taxi driver understood the English word. So, off we went. By this time, I was no longer surprised that the car we were in was a Chevrolet since the US manufacturer’s decision to build an assembly facility in Uzbekistan almost two decades ago ensured their vehicles’ affordability in the domestic market, ensuring their ubiquity on roads throughout the country today.

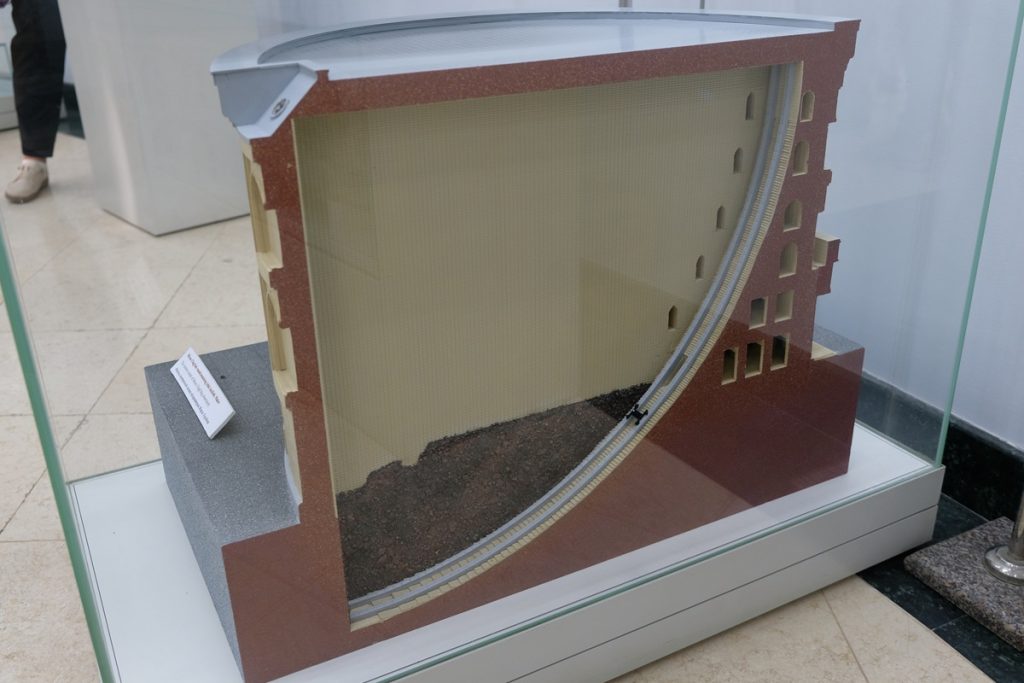

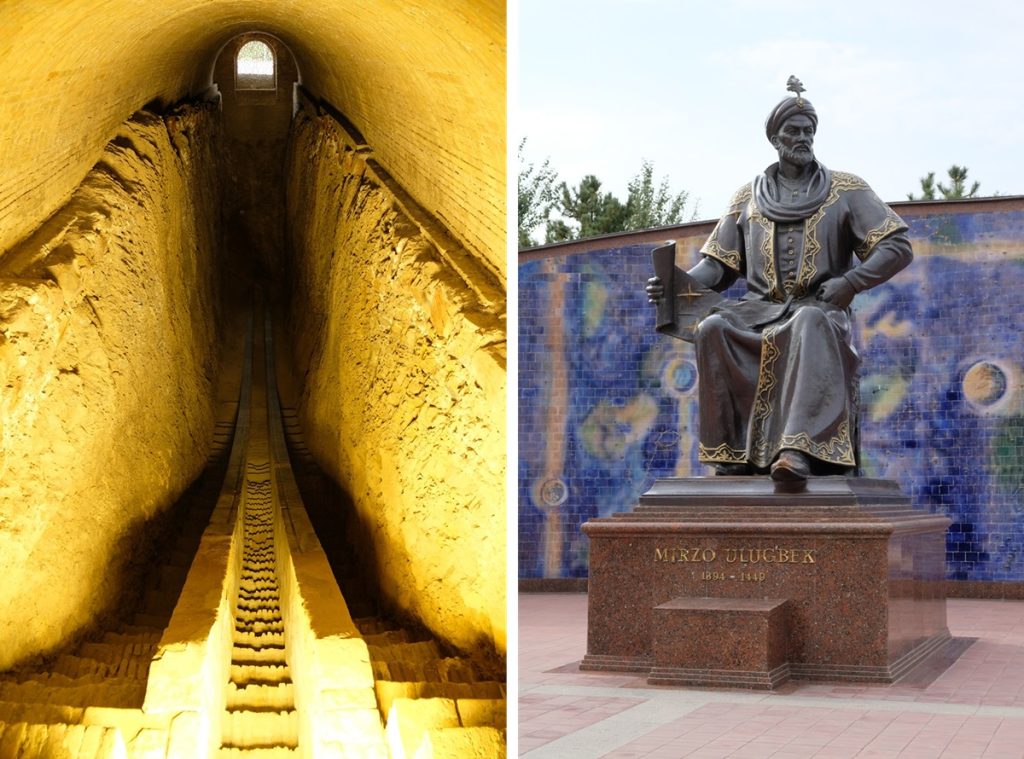

Later, the taxi driver dropped us off near a large statue of Ulugh Beg, seated on a pedestal in front of a blue backdrop depicting planets and constellations. To its left were the steps to the ruins of what used to be a colossal structure which produced among the most accurate measurements in astronomy at that time, from the length of a solar year to the Earth’s axial tilt. The Timurid ruler himself, out of his love for science and mathematics, probably preferred to spend more time at this place rather than governing his empire, which is why he only reigned for two years before being assassinated. Today, only the lower parts of the once massive sextant of the observatory remain, and a small museum within the compound provides information on Ulugh Beg’s achievements in astronomy.

Long after his death, Ulugh Beg’s works continued to be studied as they were translated into different languages by European intellectuals. However, it wasn’t until 1908 – almost five centuries after it was constructed – that what was left of the observatory finally saw the light again, following excavations carried out by Russian archaeologist Vassily Vyatkin. To honor the late Timurid sultan’s contributions to science, one of the craters on the Moon as well as a large asteroid were named after him, aptly immortalizing him among the celestial bodies he was fascinated with and studied fervently.

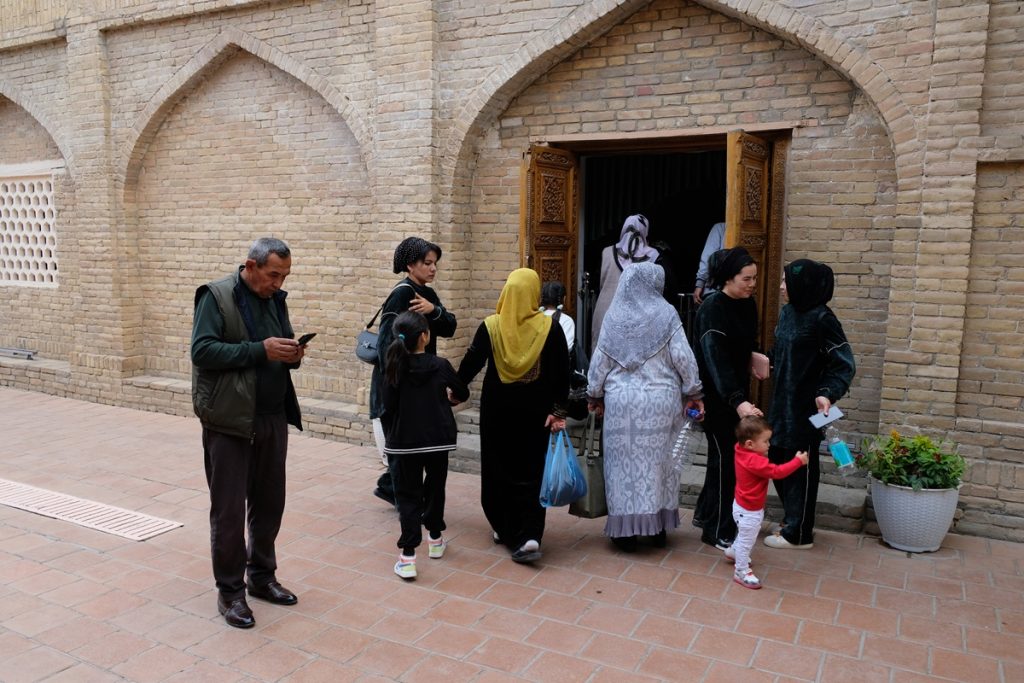

Ulugh Beg had undoubtedly left a deep impression on me, but now it was time for us to move on to the mausoleum of Daniel who had lived centuries before the time of the Timurid ruler himself. As we walked to the southwest then turned right following the calm Sieb River, the sun began peeking out from behind the clouds. In the distance, there were structures sitting at the foot of a barren hill. But this was no ordinary hill as it was exactly where the Sogdians once ruled this region from, making it the oldest part of Samarkand. As we drew closer to the mausoleum, we encountered more pilgrims who were mostly locals. We took a short flight of stairs to reach the tomb – an incredibly long one, draped in a dark cloth with Arabic calligraphy on it – while most other visitors were praying with both of their hands raised just below their faces. There was an undeniably strong sense of deep reverence toward the prophet/saint, although Samarkand is apparently not the only place claiming to be his final resting place.

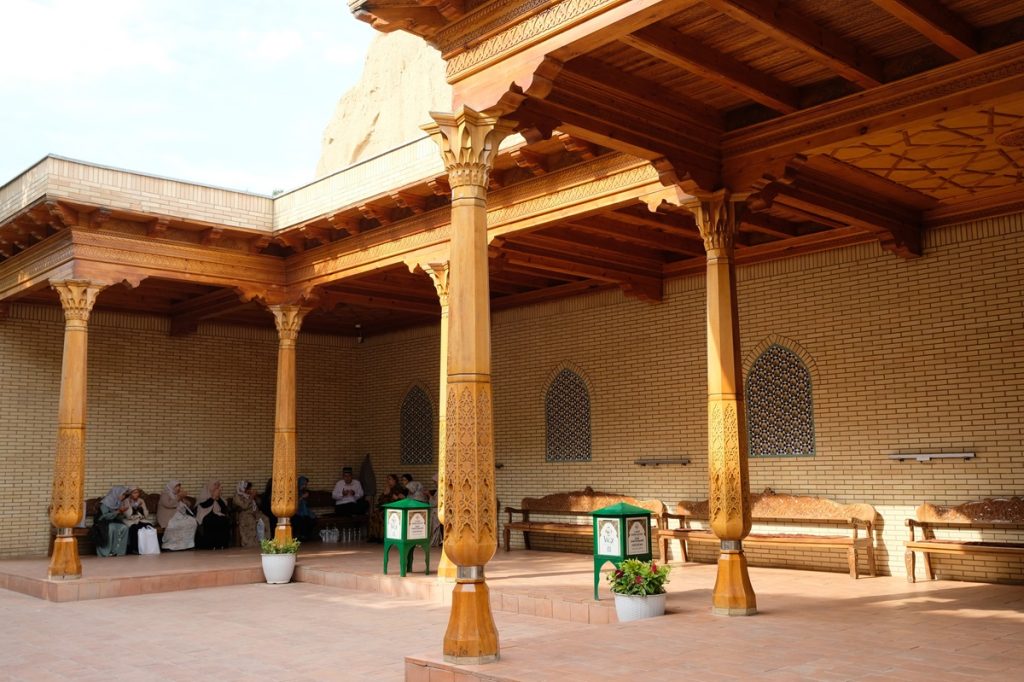

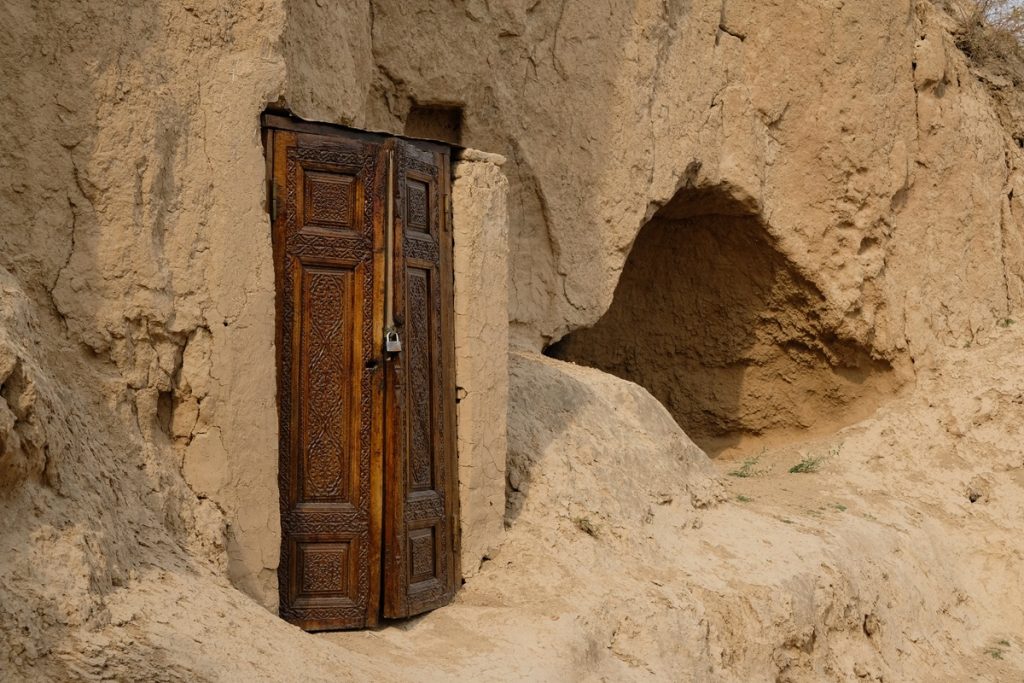

On our way to our final destination of the day, we went through the park right outside the mausoleum and were delightfully surprised to see beautiful wooden pavilions, each adorned with intricate carvings. Though not exactly the same, these works of art briefly reminded me of Java – and my parents’ former house – where such artistry is fortunately also still alive and well. We walked around the same barren hill where Afrasiab, the great capital of the Sogdians, once stood before it was taken by the Turkic Karakhanids, then Khwarazm, before the Mongols destroyed it during their expansionist campaigns in the 13th century. To untrained eyes, today this hill seems to be filled with irregular earthen mounds, but they are in fact the ruins of the former settlements. Little was spared from the destruction, and what could be salvaged was then permanently housed in a museum established in 1970 when Uzbekistan was still part of the Soviet Union.

We kept walking downhill, past bright and pretty beds of flowers, before arriving at a decidedly Soviet structure. While from the outside it came across as austere, inside the museum a wonderful and colorful world welcomed us. Displayed at the main exhibition hall were murals dating back to the Sogdian era. This was a period in history between the fifth to the ninth centuries CE when the ancient Iranian people who were adherents of Zoroastrianism controlled the strategically important trading region along the lucrative Silk Road that is now in modern-day Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan. During this time, Sogdian art reached its apex, resulting in the creation of brightly-painted murals decorating Sogdian structures. Among the most famous of these are the Afrasiab murals, depicting nations that were contemporary to Sogdia (also known as Sogdiana).

James and I joined other visitors marveling at the ornate paintings. It was mind-boggling to think that they are more than 13 centuries old, but at the same time it was also sobering to realize that many such works of art from this ancient civilization have been lost forever to the ravages of wars and conquests. From these surviving specimens of Sogdian art, we learned that the Sogdians were, in Lumley’s words, “the enablers of the Silk Road”. These frescoes show the nations the Sogdians traded with, including the Chinese, the Indians, the Koreans, the Tibetans, and the Turks. The seventh-century Chinese envoys, in particular, were depicted bringing silk to Varkhuman, the king of Sogdia. The Sogdians were so adept at trade even the Chinese (who themselves are known for their business acumen) were suspicious of them. Lumley also spoke of this Chinese saying: “when a Sogdian boy is born, they put honey in his mouth, and glue on the palm his baby hand. So that when he speaks, he speaks sweetly, and when he sees money, it sticks to his hand.”

In another part of the museum, we saw other remnants of Sogdia. However, this time these weren’t something the Sogdians created. But rather, they were the Sogdians themselves. In the past, some people from this civilization practiced cranial deformation which resulted in elongated skulls. Seeing them myself, I wouldn’t blame anyone for thinking these belonged to aliens. Overall, this rather compact museum was far more interesting than I expected it to be, thanks to its invaluable collection that provides visitors with a glimpse of ancient Sogdia. But it was time for us to head back to the city center. We followed the path that went downhill, and shortly afterward the magnificent Bibi-Khanym Mosque came into view. Samarkand was absolutely impressive, but we were ready to move on to the next ancient Silk Road city: Bukhara.