The taxi that took us from the train station weaved through the streets of Samarkand. We had just arrived from Tashkent on a two-hour journey now made possible thanks to the Afrosiyob, the first high-speed rail system in Central Asia which was named after an ancient site in Samarkand. It was only our second day in Uzbekistan after landing at the capital the night before. As I looked out of the Chevrolet car window (the US manufacturer dominates the domestic market in the country), I was mesmerized by the unfamiliarity yet curious about how different, or similar, life was like here compared to where I come from. Just before our taxi driver made the final turn to the street where our accommodation for the next few days was located, suddenly an ensemble of grand ancient structures emerged from behind the tall trees of a city park. The Registan with its three iconic madrasahs (Islamic educational institutions) was absolutely a head-turner.

During the time of the ancient Silk Road, the legendary trade routes that connected the East and the West in antiquity, Samarkand flourished as one of the most important stops. However, its location on the main course between Asia and Europe also meant that it was prone to attacks from foreign powers. Alexander the Great conquered the city (known by the ancient Greeks as Maracanda) in the fourth century BCE, and more than a thousand years later in the 13th century, it was Genghis Khan’s turn to sack the strategically important trading hub. When Timur managed to consolidate his control of Transoxiana and lands further away, he made Samarkand the capital of his empire.

Following the death of the great Uzbek conqueror, Shah Rukh – the youngest of Timur’s four sons – ascended the throne. In a departure from the way Timur ruled his dominion, the new leader put forward diplomacy, and nurtured the arts and sciences, while at the same time maintaining relative stability in his core realm. During his rule, the sultan’s son Ulugh Beg – who would succeed his father in the mid-15th century – commissioned a madrasah in the Registan in 1417, known today as the Ulugh Beg Madrasah. The institution grew to become an important intellectual center especially in astronomy and mathematics. And in an attempt to further cement the city’s status as a learning hub, and thanks to Ulugh Beg’s own passion for science, several years after the completion of the madrasah an impressive observatory was built some 4 kilometers to the northeast of the Registan square.

The Ulugh Beg Madrasah was the first to be built in the Registan, and it is today the first structure visitors will see upon entering the entire compound from the official gate in the west. Thanks to James who managed to find a relatively inexpensive yet quite comfortable accommodation a short walk away from the Registan, we took advantage of it by visiting the UNESCO World Heritage-listed group of monuments multiple times during our stay. Prior to this trip, I had seen many images of the Registan in some of the blogs I follow, and they really set my expectations quite high. However, when I finally stood in the middle of the Registan surrounded by those madrasahs, I couldn’t help but feel overwhelmed by the sheer scale of the structures and the intricate beauty that adorns them. This place looked even more magnificent in person.

To our left was the oldest of the three: the madrasah commissioned by Ulugh Beg himself. Having withstood the elements much longer than the other two, the structure immediately gave away its age. Its iwan (a vaulted space that is walled on three sides, a typical feature in Central Asian and Persian architecture) and one of its minarets were visibly leaning. Although the situation seemed concerning, I convinced myself that preventive measures must have been taken to ensure that the madrasah would remain standing for many more generations to come. As we stepped inside, we were welcomed by an open courtyard filled with trees. Since the madrasah is no longer used as a school, its hujras (studios once occupied by students who learned at the institution) have been turned into souvenir shops. Also inside the madrasah was a museum dedicated to Ulugh Beg’s achievements as well as wax figures depicting how a classroom would have probably looked like back in the day.

Back at the Registan square, another imposing madrasah stood right across from where we were. Built two centuries after the completion of the Ulugh Beg Madrasah, the Sher-Dor Madrasah was commissioned by Yalangto’sh Bakhodir, the governor of Samarkand when the city was under the rule of the Khanate of Bukhara, one of the successors of the once mighty Timurid Empire. Equally richly-embellished with geometric patterns done in the banna’i (a technique of alternating glazed tiles with plain bricks) decorative style, the 17th-century madrasah also incorporated two ribbed domes covered with turquoise tiles and wrapped in Arabic calligraphy.

Its pishtaq (the rectangular gateway to an iwan), however, is what this former learning institution is most famous for, thanks to a very unusual portrayal of earthly creatures on its upper corners. Two large felines with the stripes of a tiger and the mane of a lion seem to be chasing deer. Behind each beast is a brightly-shining sun with a human face illustrated in the disc. None of these are common in Islamic art as the depiction of humans and animals are generally shunned. Different theories emerged as an attempt to guess the artist’s intention behind this unorthodox undertaking, but the real answer might have forever been lost to the ravages of time.

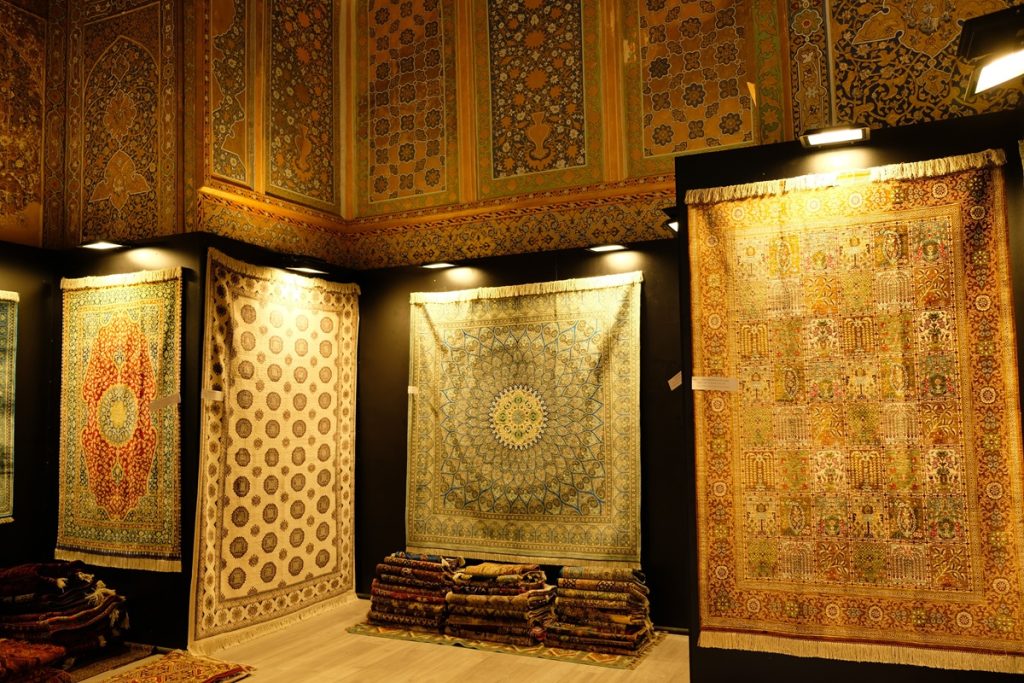

Before stepping inside the madrasah, it’s a good idea to take a look at the two niches situated to the right and left of the pishtaq. One houses an exhibition of Uzbek silk carpets, while the other is purportedly the final resting place of a revered Islamic leader. Inside the madrasah was a familiar layout like what can be found at the courtyard of the Ulugh Beg Madrasah, complete with souvenir shops occupying the hujras. When we went back to the main square, standing on the raised platform on which the Sher-Dor Madrasah was constructed, we gazed upon the youngest of the ensemble: the Tilya-Kori Madrasah. Built just a decade after the completion of the former, this three-century-old monument happens to be where one of the most impressive and important structures in the entire compound is located.

Situated right at the center of the ensemble, the Tilya-Kori Madrasah is the final structure built around the Registan square. It is distinguishable from the other two by its smooth turquoise dome that sits on the west side of the former learning institution. Once we walked past its monumental pishtaq, a large open-air courtyard was presented before our eyes. It was as if the trees and benches waved at us to come closer to soak in the peaceful ambiance. But our attention was drawn to somewhere else: the very structure underneath the same dome that gives this madrasah its iconic appearance. We followed the steady stream of visitors entering it, and once we were inside, we were stunned, our mouths agape in fascination.

Every inch of the wall all the way to the ceiling was covered in the most exquisite profusion of gold-and-blue embellishments. At first, I was overwhelmed by what I saw as I kept looking up just like everyone else around me. Then, I reminded myself to start taking photos, but I didn’t know where to begin. Eventually, after a few shots, I gradually got a grasp of the space, which was once a mosque. The kundal painting technique used to decorate the former prayer hall’s ceiling was so marvelous it made the flat surface appear as if it followed the contour of the dome above it. Apparently, this technique is still practiced in neighboring Tajikistan today.

Like the Sher-Dor Madrasah that was constructed on the ground of a khanqah (a Sufi lodge) from the Ulugh Beg period, the Tilya-Kori Madrasah was also erected on a plot of land once occupied by an older structure – in this case a caravanserai. However, whether one was part of a camel caravan that stayed in this type of accommodation, an explorer who helped to facilitate cultural exchanges between Europe and China during medieval times, or a modern-day visitor arriving in a bus or a taxi – like us – it is almost certain that the beauty of the Registan and its madrasah(s) would have left a deep impression. This centuries-old square was beautiful at dawn, in the morning, in the afternoon, and at night. And that was exactly what James and I did: we visited this jewel of the ancient Silk Road multiple times to see how it looked under different light conditions throughout the day. We were always awestruck no matter how often we returned.