When one strolls around the downtown area of Samarkand, the Registan will undoubtedly take the spotlight. It is to Uzbekistan what Machu Picchu is to Peru, the Great Pyramid of Giza is to Egypt, or the Great Wall is to China. Simply put, they all belong to an elite club of the world’s most impressive and awe-inspiring ancient sites. However, I’m not talking about the Registan just yet as I’m inviting you to take a look at another equally magnificent monument from the past that left me wondering: why was it built on such a scale?

Just a few hundred meters to the northeast of the crown jewel of modern Uzbekistan’s tourism industry is a gigantic mosque in a partially ruined state that could only have been conceived by rulers with lofty aspirations. In this case, it was none other than Timur himself. In 1399, the great conqueror of nations along the ancient Silk Road ordered the construction of a new mosque in Samarkand, the new capital of his rapidly expanding empire, to probably impress both his own subjects and foreign dignitaries alike. Other historians, however, believe it was in fact Timur’s wife, Saray Mulk Khanum, who gave the order.

The pace at which Timur (or his wife) wanted the new mosque to be completed was ambitious, to put it lightly. Since the beginning, the project already faced several problems, including ones related to the building’s structural integrity. When the mosque was nearing completion, Timur was purportedly not satisfied with the almost-finished edifice and instructed adjustments to be made. Consequently, parts of the mosque had to be reconstructed and reinforced to suit his taste. However, Timur’s vision for the structure proved to be way ahead of what construction technology in the early 15th century could provide. And unfortunately, he didn’t live long enough to see the completion of this expensive undertaking, which was then named the Bibi-Khanym Mosque, after Timur’s wife.

Ribbed domes are one of the most unique characters of Timurid architecture

There is something so attractive about this style of calligraphy on the tiles

Completion, however, is something this mosque has never seen. The Timurid Empire eventually collapsed in the early 16th century, paving the way for other regional powers to carve out the lands once consolidated under the rule of Timur and his descendants. Almost a century later, when Samarkand was under the control of the Khanate of Bukhara, an edict was issued which practically ceased all construction work at the Bibi-Khanym Mosque. Gradually, the building deteriorated. This was further exacerbated by the multiple earthquakes that rattled the region over the centuries. What remained of the edifice was then stripped of its building materials by the local residents to be repurposed into other smaller structures. It wasn’t until 1974 when Uzbekistan was part of the Soviet Union that reconstruction of the mosque was taken.

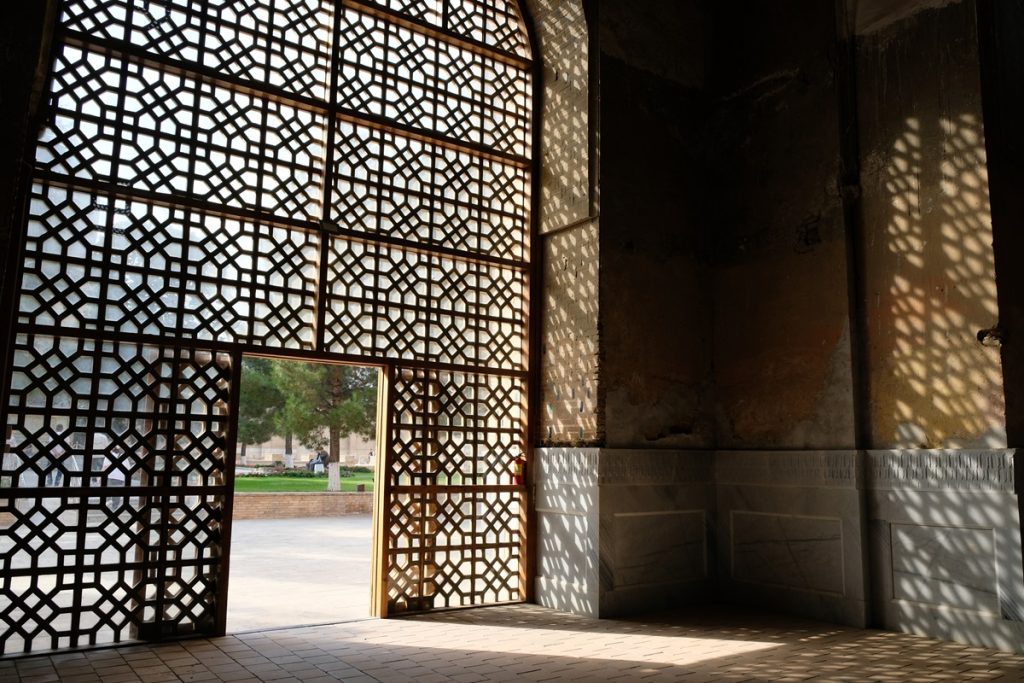

Even if you find yourself walking down the streets of downtown Samarkand today without knowing the history of the Bibi-Khanym Mosque, its immensity will not escape you. Standing in front of the outer walls of the compound, we were awestruck by the sheer size of its pishtaq (main gateway). And when we went to the inner courtyard, the scale of Timur’s ambition became even more evident. At the center of the open space was the largest Quran stand I have ever seen, enclosed in a protective glass/acrylic cover.

Toward the end of our two-week trip across Uzbekistan last October, we came across a model of the Bibi-Khanym Mosque at the Amir Timur Museum (also called the State Museum of the Temurids) in Tashkent and we were blown away by how the mosque was intended to look like. The height of the pishtaq that visitors see today is only around half of the mosque’s original main minarets.

Despite its imperfections, it’s unsurprising that the Bibi-Khanym Mosque had a far-reaching influence on the Islamic architecture across Central Asia and the surrounding regions, especially to the south. Its bricks might have started falling even before its doors were opened for devotees. But it was remarkable nonetheless, a source of inspiration for successive Timurid rulers who left their own marks in Samarkand and beyond.