Hong Kong is a calm, slow, idyllic, low-rise, and bicycle-friendly place with lots of greenery and nice white-sand beaches. Sounds hard to believe? That’s because I’m not talking about the Hong Kong most people know: a dense metropolis and shopping destination whose skyline is filled with tall skyscrapers and glitzy malls. Out of the city center, in the countryside and on the small islands that surround Hong Kong Island – where the central business district is located – a very different side of the territory thrives, providing visitors and city dwellers with a respite from the cacophony of downtown Hong Kong.

From picturesque beaches in Tai Long Wan to a traditional village in Lai Chi Wo and the boulder-studded hills of Lamma Island, Hong Kong’s landscape is so diverse it will surprise anyone who only expects to see modernity in this former British colony. Of all the small islands within Hong Kong’s territory, Cheung Chau is probably the most famous, which is the reason why it’s only on my fifth visit to the city that I finally make a detour to what is colloquially known as the “Dumbbell Island”, thanks to its shape. On a sunny day in late December, after meeting up with one of James’s high school friends over a satisfying full English breakfast in the city, we leave for the Central Ferry Pier and take the boat departing to Cheung Chau.

Almost one hour after gliding through the calm water with Hong Kong’s high-rise buildings slowly disappearing into the horizon, the ferry’s engine turns calmer as we approach the pier on Cheung Chau. Its appearance couldn’t have been a starker contrast to that of Hong Kong Island’s. Instead of skyscrapers, there are only two- to three-story houses in the main town, and as opposed to the reclaimed coastline of the main island’s northern side, the beach on Cheung Chau is entirely natural. Everyone, including us, gets off the board in an orderly manner – there’s no rush, just a jovial feeling most passengers share.

We arrive at a wide open space, a small plaza if you will, surrounded by shops, restaurants, and houses. Fried ice cream. A banner showing the flavors of this improbable dessert catches my attention at one side of the plaza, and soon enough James talks to the vendor in Cantonese and orders two lychee fried ice creams. How do you fry something that melts at room temperature? My curiosity does not last long as I watch the vendor unwrap two white balls from a freezer, poking two wooden sticks into them, and deep-frying them in hot vegetable oil that has darkened. Apparently the mochi-like outer layer protects the cold ice cream inside and helps soften it slightly to make it easier for immediate consumption. The now yellowish ball tastes as good as it is odd, and I secretly wish to have another one with a different flavor.

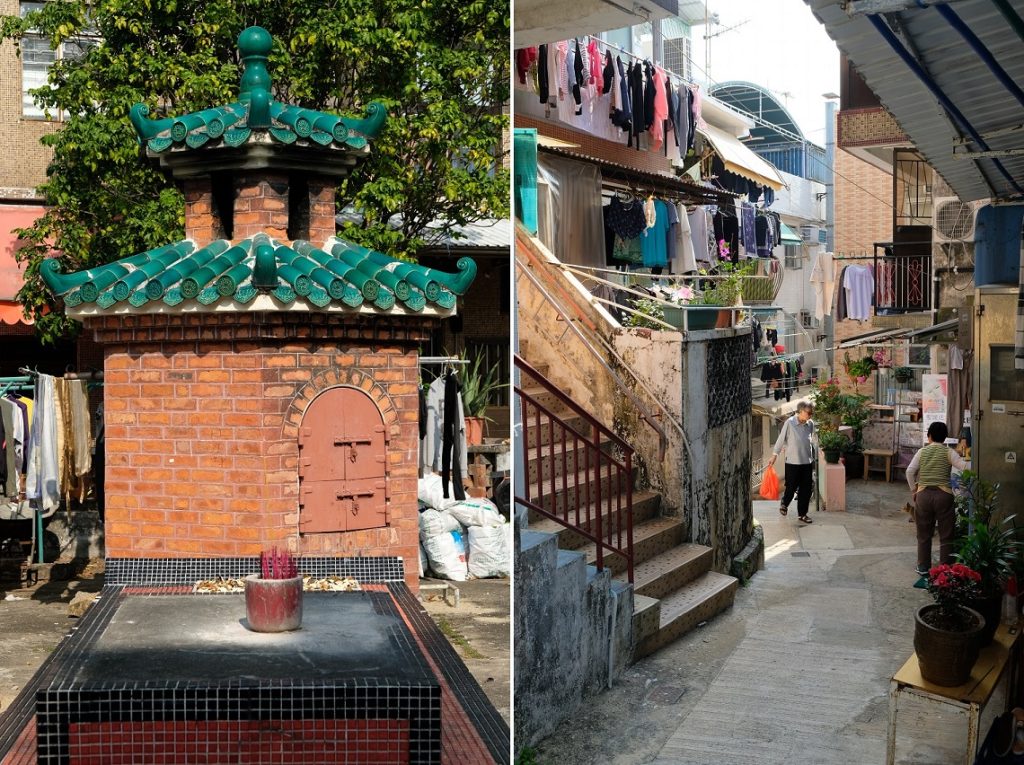

Still full from the big breakfast and refreshed by the fried ice cream, we start exploring Cheung Chau on foot, one of only two ways of getting around the island – the other being by bicycle. On a leisurely stroll, Cheung Chau looks like a place where life seems to take a much simpler and less demanding form than on Hong Kong Island. People walk slowly, the streets and alleyways are mostly quiet, and local shops still dominate the island’s retail scene. Every now and then a handful of places stand out among the others: a small Chinese temple with shiny teal roof tiles is tucked amid simple houses; a plant- and flower-filled front yard of a house makes the property the prettiest among its surroundings; and a cat-themed large banner depicting our feline friends taking the place of the protagonists and characters of some of the world’s most famous artworks.

However, underneath the benign appearance of modern-day Cheung Chau lies a history of a fearsome pirate whose ships once posed a great threat to the Qing dynasty. In the early 19th century, a time when the Pearl River Delta in southern China was already busy with international trade, a Cheung Chau-based pirate by the name of Cheung Po Tsai with his 600 ships and 50,000 men created a serious headache for the Qing imperial navy. In September 1809 the pirates captured a Portuguese trade ship sailing from the island of Timor and killed all of its crew members, an event that sparked a punitive expedition by the European power, whose local outpost was in nearby Macau. A few months later, Cheung Po Tsai finally surrendered to the Portuguese navy and handed over hundreds of ships and thousands of weapons. However, he was granted amnesty from the Qing dynasty government who then appointed him as a colonel to fight other pirates.

Walking around Cheung Chau today, however, one could be forgiven for ignoring its turbulent past since the island is now a very laid-back place. In 1997, the year Hong Kong’s sovereignty was transferred from the United Kingdom to China, a “Mini Great Wall” was constructed at the southeast corner of the island – the name was given thanks to the granite railings’ vague resemblance to the Great Wall of China. Along the 850-meter route, uniquely-shaped rocks are strewn all over the coastline, carved by the elements for aeons. And just like the names people gave to the karst formations along the Li River in southern China, it requires a good dose of imagination to see why the Rock of the Ringing Bell, the Vase Rock, the Human Head Rock, the Tortoise Rock, the Elephant Rock and the Rock of the Serpent, among other natural formations along Cheung Chau’s Mini Great Wall, were given those names.

While making sense of the rocks’ names proves not to be an easy task for me, I’m most intrigued by the unexpected aroma we encounter on this part of the island. As James and I walk further up the trail, the rather humid air is permeated by a sweet scent that wafts into our noses. My brain tells me it’s the smell of honey, but I look around and see nothing that could indicate the presence of a beehive or honeycombs. Maybe the scent happens to emanate from one of the plants which I can’t identify, or maybe someone happens to be carrying honey for whatever reason to this corner of Cheung Chau, although I prefer to think it’s the former.

From the Mini Great Wall, we continue our exploration of the island on foot to Yuk Hui Temple, an 18th-century Taoist temple dedicated to the sea god, Pak Tai. Today it is more famous as the venue for the annual Bun Festival where bamboo towers are erected and covered in buns. In the past, the event was held to keep the island’s fishing communities safe from pirates. As marauders have long vanished from the surrounding waters, the festival has now become a celebration of the local culture as well as a unique spectacle for visitors. The seven-day festivity is usually marked with a three-day abstention from meat, a tradition the local McDonald’s also takes part in by providing veggie burgers during this period.

Not far from the temple is an interesting small shop we happen to stumble upon, thanks to its clean and minimalist look. We decide to go inside Island Origin where a local artist, who we later learn is the owner of this business, is making a sketch for his next work. Ar Sai Hong Shek, or Ar Sai for short, welcomes us enthusiastically and lets us take a look at the beautifully-designed shirts, postcards, and other small souvenirs in the shop. We’re instantly drawn to a design with a fish at the center. Ar Sai explains that it pays homage to the island’s generations-long salted fish-making tradition. He elaborates on other elements of the design, including depictions of the towers of buns, Chinese junks, houses on the island, and nature. Another design speaks of the owner-and-designer’s personal journey symbolized in the form of a totem.

As the sun begins to dip toward the western horizon, we take a stroll along the island’s waterfront promenade, filled with seafood restaurants and women drying out things that look rather peculiar. James inquires in Cantonese about what they are making, and a woman explains that what we’re seeing is in fact orange peel. “It’s for traditional Chinese medicine,” James relays back to me. On the one hand, this scene is a testament to how Cheung Chau’s residents are continuing the traditions and practices of previous generations. But on the other hand, independent retailers like Island Origin might hint at the kind of businesses that will flourish on Cheung Chau in the future. Some things will probably last longer than what people predict, but change itself is inevitable. At least for now, it’s not the winds of change we feel on this island, but rather the gentle breezes of the South China Sea.