From the balmy Mediterranean Sea to the snow-covered mountains of Lebanon, the magnificent Roman ruins in Baalbek to the spectacular rock city of Petra, and the scorching heat of Jordanian desert to that of the political climate in Jerusalem – figuratively speaking – the natural and cultural landscape in the Levant is as intriguing as it is diverse. Comprising what is now Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel and Palestine, the Levant is probably among the most highly-contested pieces of land anywhere on the planet, thanks to its convoluted history – a result of the mixing of religious conservatism, tribalism, colonialism, right-wing nationalism and contemporary geopolitical agendas. However, as contentious as relations among these nations can be, when you peel away the outer layers of communal identities that often come to the forefront of any political issues, arguments and strife in this part of the world, you’ll understand that these peoples have far more things in common. And as neighbors who inhabit the same corner of the Middle East, food is one of the things the Levantines share.

After checking in to our hotel in Beirut’s Sodeco neighborhood, the first thing James and I did was finding a place to have lunch. Located just half a kilometer away from where we stayed, Al Falamanki – a beautiful restaurant with a homey village feel – was our choice. Still feeling tired after the long flights from Jakarta (including a stopover in Doha), we ordered quite a lot of dishes that could probably feed three to four people. But that was just our excuse. We had eggplant with pomegranate molasses; tabbouleh (a Levantine salad made from finely chopped parsley, tomatoes, mint, onion and bulgur then seasoned with olive oil, lemon juice, salt and pepper); labneh (a thicker version of Greek yogurt, made from cow’s milk); fried kibbeh (made from bulgur, minced onions, ground meat and spices) in yogurt with coriander, garlic and pine nuts; as well as some other dishes I can’t remember.

On another day in the Lebanese capital, we met Mahmoud, James’s friend from his days in Salamanca, Spain. It was him who helped me with the invitation letter, one of many documents I had to present to the Lebanese embassy in Jakarta to get a visa. Mahmoud and his Argentine wife Vani met us for dinner in Hamra, a district in the western part of Beirut filled with restaurants, cafes, shops and hotels. At first, they took us to T-Marbouta, a trendy place that was unfortunately packed to the brim when we got there. But the good thing about going out with locals is that they know their city well, so James and I followed them to Mezyan, another restaurant that was just down the street. They ordered all these different Lebanese delicacies, some new to us, others familiar but with a twist. The beetroot hummus fell into the latter category, and James and I agree that it was among the best dishes we tried in Lebanon. It was so smooth, creamy and well-balanced. Unfortunately, I didn’t take any photos of the food as I was distracted by our hosts’ sweetness and playfulness toward each other, which was very fun and heartwarming to watch. The next day, James and I were on our own exploring Beirut, and we decided to try our luck with getting a table at T-Marbouta, which we did. At this point, it became more and more clear to me how Lebanese cuisine emphasizes the freshness of vegetables and herbs, with that kick of tanginess in the overall flavor of a dish which varies from one restaurant to the other.

Dolma (stuffed grape leaves) at T-Marbouta

A modern interpretation of kibbeh mloukiyeh

T-Marbouta’s fatteh

To delve deeper into the culinary scene of the Lebanese capital, we joined a full-day walking tour focusing on Beirut’s food heritage. Founded by Bethany Kehdy, a cookbook author and an expert on Lebanese cuisine, the tour started in front of a breakfast joint called Barbar in a part of Hamra. This neighborhood seemed to be the stronghold of the Amal Movement, the largest Shia political party in Lebanon, given the plethora of the party’s flags strewn across the buildings and over the streets. James and I were the first to arrive, then followed by a Brit, an Aussie, and Bethany herself.

“This is not our first stop in this food tour,” Bethany said to us, to my disappointment because while waiting for them to arrive, I was salivating over all the different kinds of bread that were being made at Barbar. We soon started walking eastward to a quiet neighborhood called Zokak el-Blat. Our first destination? A small bakery called Ichkanian specializing in Armenian lahmadjun or lahm bi ‘ajin/lahmeh bi ajjine in the Lebanese dialect of Arabic. Bethany ordered the standard meat and vegetables lahmadjun as well as the meat and pomegranate version for us, and the baker in a fast and precise movement prepared our flatbread in no time. A staff member then folded them in half, rolled them, and wrapped each of them in a paper, and we were good to go. Outside the bakery, I took a bite of my first-ever lahmadjun, and I was blown away. While the standard one was really good, for me the star was the other one with pomegranate molasses which gave this traditional snack a satisfyingly sweet and slightly tangy flavor.

As we continued walking, Bethany explained the story of some derelict buildings that we saw along the way. During the Lebanese civil war, the belligerents fought over Beirut’s skyscrapers as taking control of them was seen as giving them an upper hand over the others. She also recalled the days when she and her family had to move to a village high up on the slopes of the Mount Lebanon range to escape the brutality of the war.

It was mostly cloudy throughout the day, and barely a few blocks away from Ickhanian bakery, what began as a drizzle turned into a torrential downpour. Although we were supposed to do the tour on foot, Bethany decided to hail an Uber to get us to our next destination so that we wouldn’t have to spend the rest of the day soaking in wet clothes. Soon, we arrived at a row of falafel joints on Damascus Street. Bethany went inside one of them and bought some falafels, but then she took us to nearby Falafel Aboulziz to have the ones she bought earlier and see how they compared to what Aboulziz makes. Falafel is usually made from either chickpeas, fava beans, or both, and is usually served in pita bread. But what makes Aboulziz’s special was that his were made mostly from chickpeas – some places use more fava beans as they are cheaper. After finishing mine, I looked out and just across the street was an abandoned building riddled with bullet and shrapnel holes, another reminder of the devastation the 15-year civil war had brought upon the city and its people.

We then moved to another place a few minutes’ walk southeast of the falafel joint and arrived at a dessert place in Sodeco, not too far from our hotel. As we entered the premises, heaps after heaps of baklava in different sizes and shapes welcomed us. This very much reminded me of my trip to Istanbul back in 2013 when I tried the very sweet pastry for the first time. Bethany ordered some for takeout, then led us across the street to Sodeco Square, a development project that turned a derelict patch along the former Green Line (a no-man’s land that separated Beirut’s east and west during the civil war) into an upscale commercial and residential complex. We enjoyed the sweet (but not overly so) baklava with Lebanese-style cardamom coffee.

The sun had come out again by the time we strolled into the predominantly Christian district of Achrafieh. It was here that Bethany led us to a small, nondescript joint which turned out to be one of the most celebrated ice cream parlors in Beirut. Widely known as Hanna Mitri, and named after the father of the current owner who opened the business in 1949, this place has never shut its doors, even during the civil war. Each of us was handed out a pile of ice creams and sorbets with different colors, textures and flavors, from pistachio and caramelized almond to rose water, apricot, strawberry and lemon. And it was clear that I wasn’t the only one enjoying this refreshing dessert so much as the others in the group seemed to also be savoring the complexity of all those layers that tickled and pleased our taste buds.

Layers of sweet goodness

The end result

After this brief stop, Bethany ushered us into a nearby shop selling artisanal olive products – from olive oil to olive jam, pickled olives, as well as olive oil soap – then to a local restaurant to have shawarma, probably among the most well-known Middle Eastern dishes in the world. At the end of the tour, Bethany would take us to the Armenian quarter in Bourj Hammoud further east. But on our way there, we stopped at a small diner on Armenia Street that was manned by an elderly Armenian woman who, as Bethany said to us earlier, “cooks her food using a hairdryer.” We were the only customers when we went inside her modest place, and as soon as Bethany placed our order, the action began. She started by chopping some meat as well as sheep’s tail fat into small cubes. Then they were all neatly fitted onto metal skewers, placed over hot charcoal, and … blown with something from a compartment that was plugged into an electric socket. It was the hairdryer! As much as the cooking process was fun to watch, the end result itself was a delicious dish where the tender and succulent meat went well with the grilled tomato and other ingredients.

From this place, we kept walking east, crossing the Beirut River to arrive at the heart of the Armenian community in the Lebanese capital. The significant number of ethnic Armenians in Beirut (and in many parts of Lebanon) can be attributed to Armenia’s turbulent history under the Ottoman rule which pushed many Armenians to leave their homeland and resettle elsewhere across the globe, including in then French-controlled Lebanon. Generations after this exodus, Armenian culture is now very much an integral part of modern Lebanon, with the former’s food now deeply embedded into the Lebanese culinary scene. At a restaurant on a narrow alley in Bourj Hammoud, the five of us were joined by a group of Americans – mostly from Oregon – led by Bethany’s brother, Eli, who had just finished guiding a day-trip outside Beirut. Over a long table we all sat down together and shared our experiences while the staff in the kitchen were busy preparing our dinner. Then, one by one, delectable-looking Armenian dishes arrived at our table. From manti (Armenian dumplings), soubereg (cheese in filo pastry), and many more dishes whose names I can barely remember. One thing I noticed from all the things I ate that night was the fact that they were generally more spicy and bolder in taste than other foods we had tried so far in Lebanon. This dinner alone has propelled Armenia high up the ever-expanding list of countries I want to visit in the future.

My culinary exploration in Lebanon was a success. I don’t recall ever trying anything that didn’t taste good throughout our week-long stay in the country, from Beirut to the snow-covered village of Al Arz and the historic city of Baalbek. In the Lebanese capital we were lucky to have locals to bring us to places that serve good Lebanese food, and we also made the right decision of joining the culinary tour with Bethany. But even when we were on our own, we always came across places that did decent food. From the outside, Zaatar W Zeit seemed to be just another fast food restaurant chain. But at their branch in Sodeco, we quickly found out that it’s simply not comparable to McDonald’s or KFC. On our first visit, we ordered all kinds of dishes, so much so the waitress had to stop us and said that it would be too much for the two of us. So we followed her advice and dropped a few of our initial choices. Only after our manousheh (or manakish in plural) came did we realize what she meant with ordering too much food. Liberally sprinkled with za’atar (a dried herb or spice mixture widely used in Levantine cooking), the flatbread was as delicious as it was filling. On our second visit, we tried another kind of manousheh, this time with za’atar and Akkawi cheese (a type of cheese originating in the city of Akko, or Acre, in modern-day Israel). It was equally good, if not better, than the first. Lebanese za’atar was so good we didn’t mind having it in just about everything we ate in Lebanon. However, Bethany told us that the za’atar from Jordan is actually better, which really intrigued us and became part of the reason we decided to travel to the latter six months later. Impulsive? Maybe. Did we regret it? Absolutely not, for we learned that Jordanian food could well be among the world’s most underrated cuisines. That’s for the next story.

With all the delicious dishes they serve, I really wish Zaatar W Zeit opens a branch in Indonesia

Bread and pastries from a local bakery near our hotel in Beirut

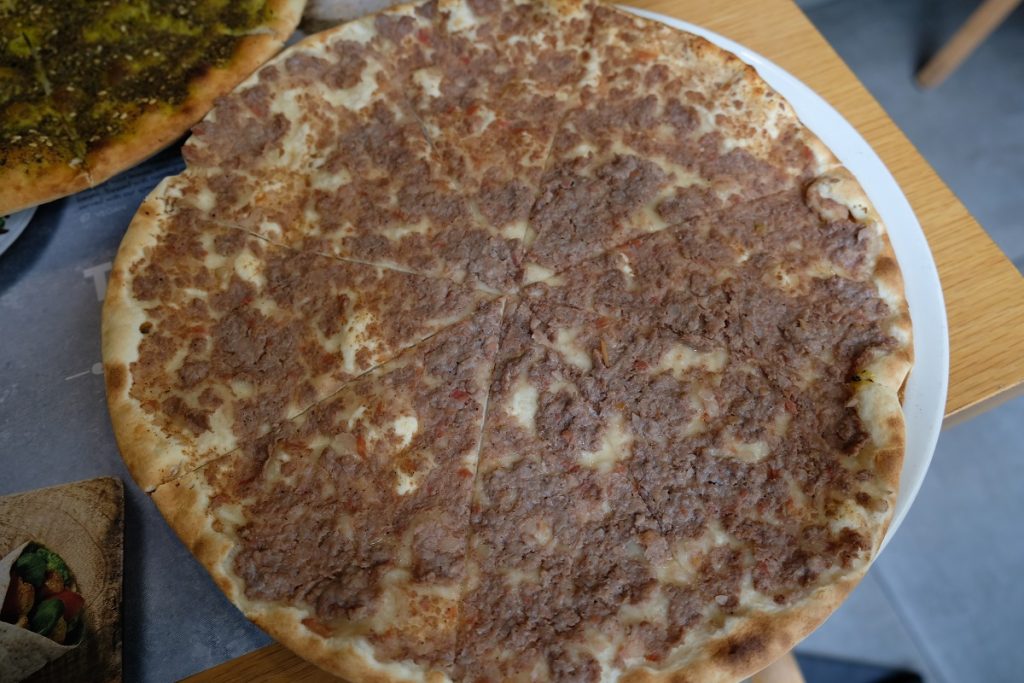

Pizza with sujuk (dried spiced sausage)