These days, reading about the resurgence of racism in many parts of world often makes me wonder what went wrong since the abolition of apartheid in South Africa, the election of the first African-American president in U.S. history, and other milestones which showed that more and more people had embraced tolerance and inclusiveness. In a time like this when racism seems to gain momentum again, it is worth reminding ourselves what we can do as ordinary people to fight the increasingly ugly discourse among us.

Sure, we all know that learning about the world and important historical events can help us get a better understanding about why things are what they are today – although there will always be people who believe that the alternative “facts” they read are indeed the truth. Furthermore, many of us agree with the notion that traveling is among the best ways to combat prejudice, especially when we are confronted with cultures and values so different from ours, and people whose skin color, eyes and hair look nothing like what we’re used to seeing. However, there are those who only tell stories about how ugly and backward the places they went to were, and always brag about the supposed superiority of their own countries. But perhaps (un)surprisingly, there are also people who think that other countries are worse than their own even though they haven’t traveled abroad at all.

A trip I did two years ago to South Sulawesi in Indonesia recently popped up in my mind as I see just how ignorant a lot of people are when it comes to race. Hidden beneath the limestone peaks of what is believed to be among the largest karst formations in the world is an invaluable collection of prehistoric cave art that have been hidden from plain sight for aeons. These artworks, tens of thousands years old, can teach us that not only is the concept of racism obsolete, but also absurd. To reach these caves one needs to take a small boat which will then go through meandering rivers occasionally shaded by palm trees. Towering karst peaks emerged as James and I ventured deeper into Rammang-Rammang, part of the Maros-Pangkep karst mountains, and at times our skipper expertly navigated the boat through narrow corridors which opened up to another impressive view of the landscape.

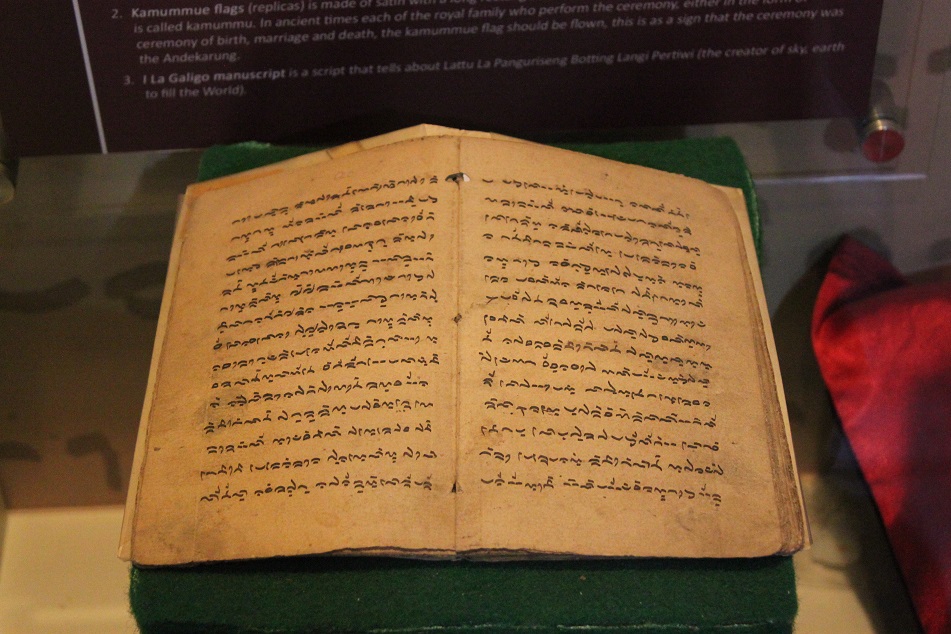

Ideally, a visit to this part of Sulawesi to get a glimpse of the cave art requires a few days with a local guide who knows exactly how to reach the caves. However, as our time was limited, we only did a half-day trip from Makassar, South Sulawesi’s provincial capital. The cave art was first studied in the 1950s, but only in 2014 following a radiocarbon dating conducted on the surfaces of the caves on which hand stencils and paintings were made did these prehistoric artworks make international headlines. Previously thought to be no more than 12,000 years old, the oldest hand stencil here turned out to date back to 39,900 years ago, making it the oldest hand stencil in the world to date. This discovery had shaken up the long-held conviction that ancient cave paintings originated and developed in Europe before spreading to other parts of the world. Not only has this been named one of the year’s most important scientific discoveries, but it also fundamentally challenges the Euro-centric view many white supremacists uphold and base their arguments upon.

Some people say ignorance is bliss. But this kind of ignorance is too dangerous to be taken lightly. Only when people leave their comfort zones, put aside whatever prejudice they have, and go see the world with open minds and hearts, will they learn that different things and people are not always like what they have been told. For a better idea of how important this discovery on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi was, here is a link to a National Geographic article and another by the New York Times.

Going Back to Where We Came From

Today, Rammang-Rammang is easily accessible from Makassar, Indonesia’s eleventh biggest city as well as the largest metropolis in the eastern part of the country. Makassar’s prominence as the gateway of eastern Indonesia, however, began a long time ago. In the 16th century when the Europeans had already discovered the sea routes from Europe to the Spice Islands, Makassar – strategically located on the trade route to and from the islands where nutmeg, mace and cloves originated – started growing as a major trading port in the region. Merchants from many parts of the vast archipelago (modern-day Indonesia), China, India, as well as Portugal exchanged commodities at the port. Home to the Makassarese and Bugis people, for centuries known as reputable sailors, the port was also a base for brave locals to explore the archipelago and settle in faraway places, including Malaysia and Singapore – Malaysia’s current Prime Minister is in fact a Bugis. When the Dutch joined the spice race and eventually dominated its trade in the region, they captured Makassar in the 17th century and rebuilt a fort known today as Fort Rotterdam.

The modern city of Makassar still remains an entrepot thanks to its strategic geographical position at the heart of Indonesia. Flights from the western parts of the country to its eastern cities often stop over here. The election of Jusuf Kalla, a prominent businessman and politician who is native to South Sulawesi, as vice president of Indonesia in 2004 marked the beginning of an era of rapid development in Makassar. Its airport was expanded, including the addition of another runway making it the second commercial airport in the country, apart from Soekarno-Hatta that serves the nation’s capital, to have double runways. Infrastructure aside, in recent years Makassar also saw the inauguration of the biggest theme park in eastern Indonesia.

Our stay in Makassar was too short to soak in the local culture as we made the city merely a base to explore the picturesque Tana Toraja in the highlands of South Sulawesi before flying to Ambon, the capital of Maluku (Moluccas) Province. However it would be interesting to return one day and see whether the city – located half an hour away from Rammang-Rammang which challenges the concept of racism – treats its own residents equally regardless of their race.