The Year of the Wood Snake is just around the corner, and ethnic Chinese communities across the globe are gearing up for the festive season. Families gather, people travel long distances to be reunited with their loved ones, even many shops, factories, and offices are temporarily closed despite business owners’ perceived notoriety for putting profit over people. But money is indeed one of the most important aspects in Chinese culture, as attested by James (who grew up in Hong Kong) and my Chinese-Indonesian friends. Better wealth and prosperity are among the most common wishes expressed during the Chinese New Year celebration.

In Cantonese culture, for example, the ubiquity of certain fruits, dishes, and paraphernalia that begin showing up weeks before Chinese New Year can be attributed to how they sound. In Cantonese – a language spoken in Hong Kong, China’s Guangdong Province, and by the Cantonese diaspora worldwide – the word for “tangerine” is homonymous with “luck”, “fish” with “abundance”, and “black mossy fungus” with “get rich”. Unsurprisingly, it is very common to find these served at restaurants in Hong Kong during the festivities. In Indonesia, on the other hand, lapis legit is usually eaten for the special occasion due to the many layers of the cake symbolizing an abundance of good fortune. The rich dessert traces its origins to the Dutch colonial period in Indonesia where spices from across the sprawling archipelago were added to give this layered cake a delectable twist unlike its other Southeast Asian counterparts. The Chinese community in what is now Indonesia then embraced it – a cultural adaptation (not appropriation) at its best. And don’t forget about lai see or hongbao or ang pau, the red envelope filled with money handed out by adults to unmarried members of the extended family during the celebration.

This love for wealth is also what drove a lot of Chinese people to leave their homes for foreign lands to seize business opportunities abroad. It is not uncommon to read and hear stories about Chinese immigrants and their descendants who successfully built business empires wherever they settled. This, in turn, fueled even greater numbers of people leaving the Chinese mainland to chase their own business dreams abroad. Saigon (also called Ho Chi Minh City today) and its surrounding areas were among the places that received a lot of Chinese immigrants (especially from southern China), a practice which was in fact encouraged when this part of Vietnam was controlled by the Nguyen lords. Over time, their settlements in the city, an area known as Cholon (Chợ Lớn), grew in size and population, so much so it has now become one of the largest Chinatowns in the world according to some estimates.

The residents of Cholon, however, are anything but monolithic. Contrary to what many people might think, Chinese communities are as diverse as Romance language speakers in Europe – the Italians, French, Spaniards, Portuguese, and Romanians. The southern Chinese immigrants who settled in Cholon came from different cultural backgrounds, each with its own language, customs, and traditions, including vernacular architectural styles. In one of his posts, James explains the history of Cholon, including how the area’s central Bình Tây Market came to be. But you don’t really need to be a history buff to appreciate the neighborhood’s many gems.

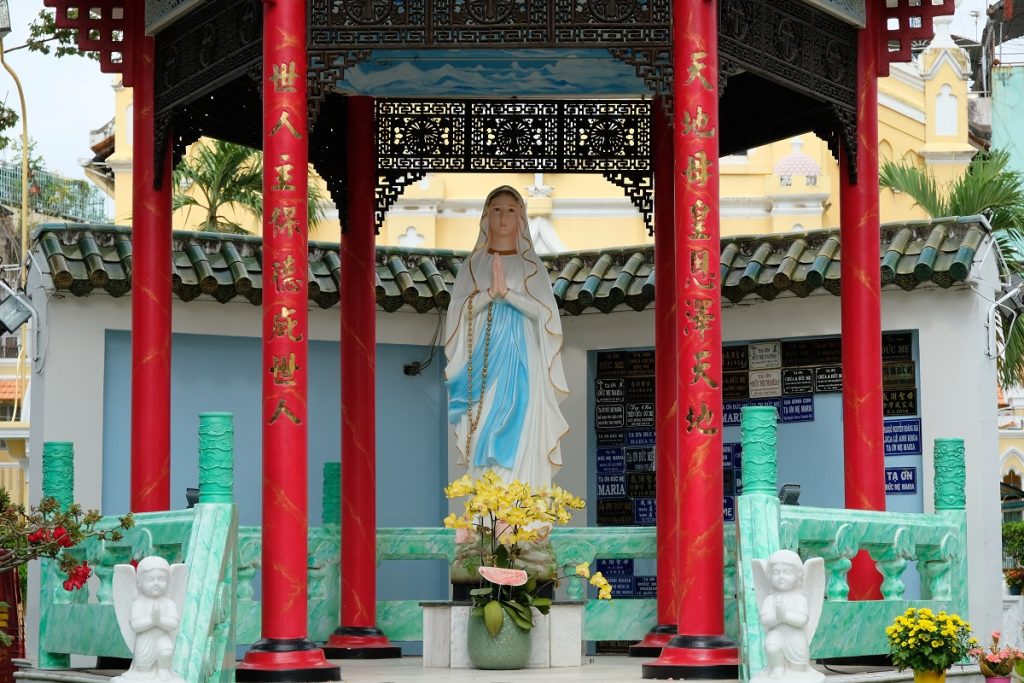

We were lucky that Len, our blogging friend who lives in Saigon, was able to take a day off work to show us around parts of his city, including Cholon. Our explorations began at the market, unmistakable for its clock tower. The entire compound was painted in a shade of yellow that is very emblematic of Vietnam and is reminiscent of ripening rice paddies. For the locals, the color represents, you guessed it, prosperity and wealth. We walked inside, which was apparently also Len’s first time, and went upstairs to watch a motley of activities below. After checking out different corners of the market, we headed to the next place some 700 meters away: St. Francis Xavier Church. The early 20th-century Catholic church is known for its eclectic design, incorporating East and West architectural elements as evident in its central courtyard where a statue of the Virgin Mary is housed inside a Chinese-style pavilion.

A few blocks away was Hà Chương Assembly Hall, a temple built by Hokkien settlers from Fujian. It is dedicated to Mazu, the sea goddess revered by many in southern China. Also in the vicinity was another place of worship commissioned by Cholon’s Hokkien community: Quan Âm Pagoda, a Buddhist temple first established in the 18th century which has undergone multiple restorations throughout its history. The architectural styles of both places unsurprisingly reminded me of the Chinese temples found in Java where the Hokkien people are the dominant Chinese community on the island.

Around 300 meters away from the Buddhist pagoda, however, was a temple that instantly rekindled my memories of Hong Kong. The Cantonese-style Thiên Hậu Temple is dedicated to Tin Hau, the same goddess the Hokkien call Mazu. To my eyes, the straight horizontal elements found on top of the roof and between the pillars are among the most discernible characters of a Cantonese temple, which happened to be the first things I noticed from the structure at this fifth stop. I particularly loved the dioramas of ceramic miniatures adorning the temple – regular readers of this blog know how I have a soft spot for such finely-crafted figures.

Finally, our sixth as well as final stop for our half-day excursion around Cholon was the recently-renovated Nghĩa An Assembly Hall (also known as Guan Di Temple), a stone’s throw away from Thiên Hậu Temple. Built by the Teochew community in the early 19th century, this shrine is used for the worship of Guan Yu, a legendary military general of the Han dynasty (third century CE) whose name was immortalized in the 14th-century Romance of the Three Kingdoms. The vibrant colors of Guan Di Temple were so mesmerizing I couldn’t stop looking up to marvel at the brightly-painted and intricately-decorated beams and rafters. Gold and red were used rather liberally, of course, as they symbolize wealth and good luck, respectively.

It was absolutely a delight to visit all these temples, a testament to the unwavering spirit to achieve prosperity shared by ethnic Chinese communities across the globe. If you happen to belong to one of them, I wish you health and may your heartfelt wishes come true. Oh, and may a lot of fortune come your way too! Happy Chinese New Year!