Conquerors must be among the most divisive figures in human history. They are often regarded as heroes by the people they represent, whose territory grows following victorious military campaigns. But on the other hand, the conquered see them either as an evil force or as liberators from much more cruel rulers. We all know well how countless triumphant conquerors have been immortalized in people’s memory through all sorts of mediums, from oral stories to inscriptions and great monuments. Among them, Genghis Khan undoubtedly ranks as one of the most illustrious, for he managed to unite different Mongol tribes and build a land-based empire that would at one point become the largest of its kind the world has ever seen.

While conquests are inherently violent, they have also proved to open new doors for commercial opportunities and promote wider cultural exchanges, as well as become a source of inspiration. More than a century after the demise of the great Mongol leader in 1227, a boy was born into a Turco-Mongol society in Transoxiana, a term coined in the fourth century BCE by another extraordinary conqueror in history, Alexander the Great, to describe a region in Central Asia. Named Timur, which means “iron” in the Chagatai language (an extinct Turkic language once widely spoken in this part of the world), the boy would eventually get exposed to stories of Genghis Khan which inspired him to be a conqueror himself.

Claiming to share the same ancestor with Genghis Khan, Timur gradually amassed support and influence by aligning himself with the right people, showing his prowess in battle, and astutely using his cultural and historical backgrounds to reinforce his legitimacy. He even went further to style himself as the awaited messiah descended from the prophetic line as he sought to be the leader of the Muslim world. Once he managed to assert control of Transoxiana, he embarked on decades of military campaigns to conquer lands beyond his core realm. Very much like what Genghis Khan had done more than 100 years earlier.

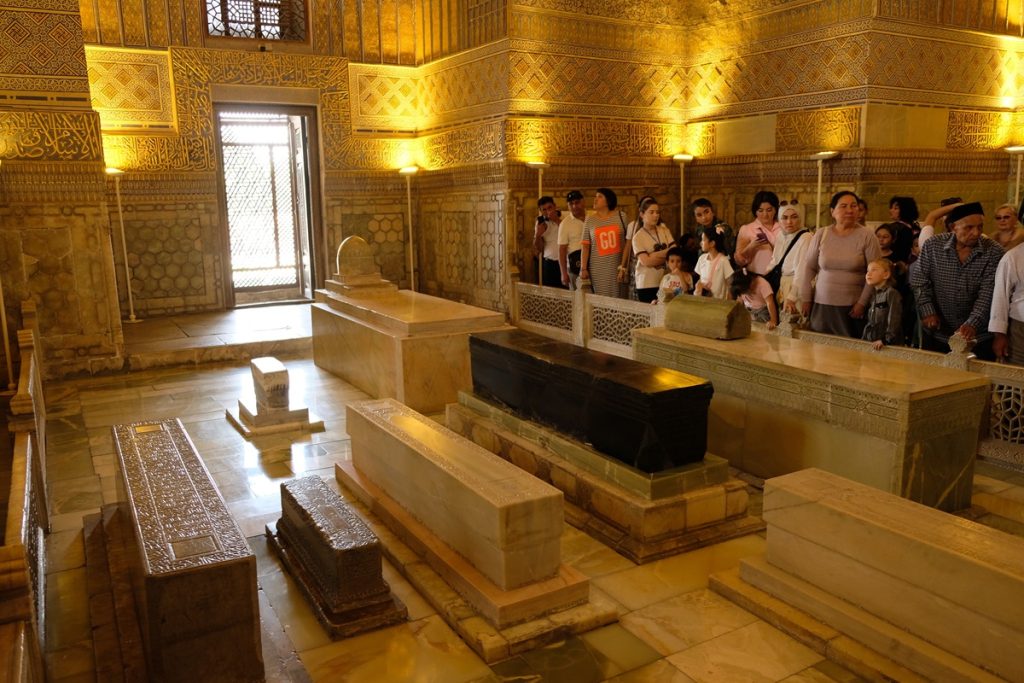

Beneath this ornate turquoise dome is the tombs of Timur and his descendants

Timur’s army marched on and subjugated Persia and the Caucasus region, invaded Delhi, sacked Damascus and Aleppo, crushed Baghdad, and defeated the sultan of the Ottoman Empire near Ankara. The seemingly unstoppable conqueror then turned his attention to the east where the Ming dynasty reigned. In the year 1404, he began his campaign to attack the Chinese in winter, uncharacteristic for a man who usually preferred to fight battles in springtime. Then, in early 1405 the unfathomable happened. The great conqueror fell ill and died before even reaching the western border of China, ending what had appeared to be an unrelenting expansion of his territory.

His body was then buried in Samarkand, which in 1370 had been made the capital of the Timurid Empire by Timur himself. Despite his reputation as a ruthless conqueror, he showed a great interest in the arts, and this is the reason why his capital was then filled with beautiful and magnificent buildings. However, this was rather expected from a ruler who wanted to showcase his achievements and impress the world. Around two years before Timur’s death, a grand mausoleum was commissioned in the capital for the ruler’s heir apparent who suddenly passed. But he had probably never imagined that just a few years later he would also be interred in the same place. Dubbed Gur-i Amir, “Tomb of the King” in Persian, the complex would then also be the final resting place of Timur’s descendants.

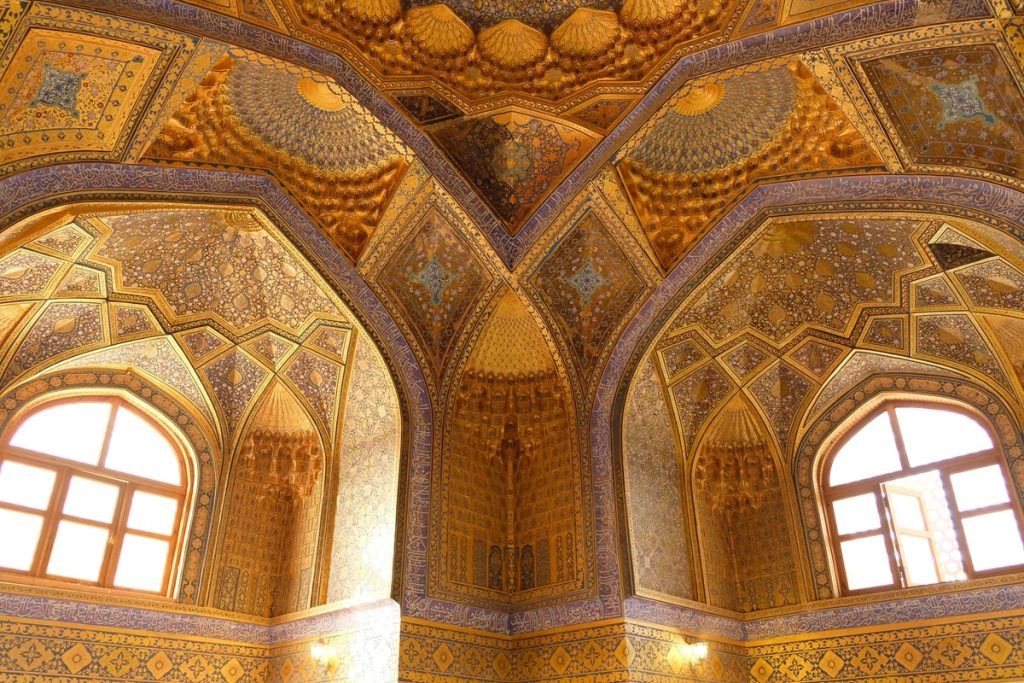

Centuries after his time, Timur is now considered a national hero of modern-day Uzbekistan, the most populous country in Central Asia. His birthplace is now the city of Shahrisabz, some 90 kilometers to the south of Samarkand where a larger-than-life statue of him stands near his former Ak-Saray Palace – according to the images we saw on the internet as we didn’t have enough time to visit this city. However, this is not exclusive to his hometown as other likenesses of him can also be found at strategically-located parks in bigger cities like Tashkent and Samarkand. While he is undoubtedly a source of admiration for the Uzbek people, others are also fascinated by him, or at least by his tomb. When we arrived at Gur-i Amir one afternoon, a steady stream of visitors came and went. Underneath the ribbed dome was a cavernous space heavily embellished in intricate ornamentations fit for the rulers of such a great empire. In contrast, the tombs themselves were much simpler in shape and decoration, belying the lofty ambitions of the men buried in this place. One such case manifested as a monumental mosque at the heart of Samarkand where I will take you next.