The world is filled with so many wonderful places, and that’s often why a lot of us travel across the globe to see and experience those sites ourselves. Most of the time they meet our expectations, although sometimes we come home feeling disappointed for various reasons – overtourism, pushy vendors, and varying states of disrepair to structures that we had seen so often on the internet or on the glossy pages of travel magazines prior to our visit, to name a few. However, there are places that, despite their popularity and the plethora of their images both on and offline, will always evoke admiration even from the most jaded travelers. And I find that Petra fits this category.

It is probably Jordan’s most recognizable landmark. Images of the Treasury (Al Khazneh) adorn the covers of a multitude of guide books on this Middle Eastern kingdom. And I believe most people, including me, who go to Jordan have Petra on their minds at the trip-planning stage and even during their stay in the country. Today, this part of the kingdom attracts around half a million tourists every year, but that was not the case for many centuries. Like Cambodia’s Angkor which was brought to a broader audience by the 2001 film Lara Croft: Tomb Raider where Angelina Jolie explores the silent and mysterious corners of Ta Prohm and dangles from tree roots to find an artifact to control time, Petra was ‘introduced’ to the world by the 1989 Hollywood blockbuster Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. It is where Indy (Harrison Ford) finds the Holy Grail as well as the background for the final scenes of the movie where Indy, his father (Sean Connery), Marcus (Denholm Elliot) and Sallah (John Rhys-Davies) escape the temple through a narrow passageway we now know as the Siq.

However, before we get to see all these places with our own eyes, James and I have to travel more than 200 kilometers to the south from Amman, Jordan’s fascinating capital. From the satellite images on Google Maps, it seems like the highway we have to take cuts through the desert almost from the very beginning at the outskirts of the city. But it is supposedly faster than taking the King’s Highway, a historic road that has been used by the armies of ancient powers to wage wars against each other, by merchants to trade commodities between cities in Egypt and the Levant, and by Hajj pilgrims to reach Mecca before the advent of air travel.

Our driver who picks us up at our hotel in downtown Amman arrives on time at 8 am, and shortly afterward he navigates his way to Wadi Musa, a small town in the country’s south which serves as the gateway to Petra. The drive feels long and, after a while, very monotonous, thanks to the endless desert as far as the eye can see on both sides of the highway. But what intrigues me most is the fact that despite this harsh environment, there are small houses here and there, peppering the arid landscape. Halfway into the journey, our driver pulls over at a shop with a restaurant and restrooms inside. The souvenirs look nice, for sure. However, I’m more interested in the book section, and end up getting myself a hardcover volume on the history and art of Petra.

Twenty minutes later we’re already back on the road, venturing deeper into the south under the scorching desert sun. I’m glad we’re in an air-conditioned car, not on a camel, but more on that in a later post. Hours later, the monotonous landscape suddenly changes. Something on the horizon comes into view: rose colored mountains through which our driver takes us. Then, a small town emerges. We have finally arrived in Wadi Musa, which means “Valley of Moses” in Arabic. This remote corner of Jordan was named after the important figure in the three Abrahamic religions due to its significance as the place where Moses is believed to have struck water from the rock for his followers. The site is now known as Ain Musa, or Moses’s spring. In its vicinity, on one of the imposing mountains, lies what is today regarded as the tomb of Aaron, the brother of Moses who’s also known as Harun in the Islamic world.

The recently inaugurated Petra Museum

A multimedia display and some of Petra’s finest artifacts inside the museum

A syncretic depiction of the Nabatean-Arabic goddess Al Uzza and the Egyptian goddess Isis

A garland frieze from the ancient city of Petra

The Djin Blocks at the approach to the entrance of the Siq

After checking in at a hotel near the town’s main roundabout and having a lunch of maqluba (a traditional Levantine dish which consists of rice, eggplants, chicken and spices cooked in a pot then flipped upside down on a plate and served), we immediately walk downhill toward the main entrance to the archaeological site of Petra, which was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage list in 1985. At the final turn, we stumble upon bigger hotels run by international chains, conveniently located just a few steps away from the gate to the ancient city. Just across the street is the Petra Museum, a sleek brand new building funded by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) and inaugurated in April 2019, six months prior to our visit.

Months before this trip, we decided to purchase the Jordan Pass which covers most of the country’s historical places with options for one-, two-, or three-day pass for Petra. Obviously we chose the longest one, for we knew we would spend a lot of time at this place that had been on our wish lists for years. After checking our Jordan Passes, the staff member at the entrance lets us in, and we find ourselves on the same ancient road which people took to enter and leave Petra two thousand years ago.

Its location at the crossroads of trade routes that branched out to Mesopotamia to the east, Arabia to the south, Egypt to the west, as well as Syria and the Mediterranean to the north made the mountainous area in which Petra was built very strategic. However, due to its harsh environment many powers in the region saw this part of the Levant as merely a barren land. When Babylonia expanded its territory westward, it is believed that this campaign pushed a group of nomadic people to the edges of the empire to this very desolate land. These people later became known as the Nabateans.

At first they found refuge in this mountainous landscape in the middle of the desert. They continued their nomadic lifestyle by setting up tents across the rugged terrain. Over time, they started digging large cisterns in the solid rock to conserve the water they collected during rare rain periods; they also carved out niches which provided them with sturdier shelters from the elements; and eventually they left their tents and settled in the man-made caves instead. They named this place Raqmu, which the Greeks then called Petra, or “the rock”, a name we still use today. Thanks to their ingenious water management, the Nabateans made a living by supplying water to passing caravans. In exchange, they imposed a levy on those foreign merchants and became actively involved in the trade of spices, silver, frankincense and myrrh themselves.

The Nabateans amassed more riches with each passing year, which brought this obscure place to the attention of the rulers of Greece, Egypt and Syria. For more than a hundred years since the fourth century BC, apart from running their profitable businesses, the Nabateans were kept busy defending themselves against invading forces who had one thing in common: an ambition to incorporate Raqmu or Petra into their own realm. However, thanks to the rocky mountains which acted as natural fortresses, the narrow and easily defendable entrance to Raqmu, and the labyrinthine passes amid the towering peaks, the Nabateans managed to drive every conquering force away from the city, therefore retaining their independence. Then, following the decline of the Greeks, and backed by a significant amount of wealth, the Nabateans eventually established their own monarchy with Aretas I who ascended the throne in 168 BC as their first local sovereign ever recorded in history.

An ancient aqueduct, a vestige of Petra’s advanced water management system

One of many niches carved out of the walls of the Siq

In the subsequent years, the Nabateans managed to expand their trade network to places as far as Hegra (in the northwestern corner of modern-day Saudi Arabia), the Gulf of Aqaba, and towns in what is now Israel. In Petra – by this time already a well-established capital of the Nabateans – this increasing wealth became more apparent with the construction of bigger and more elaborate rock-hewn houses and tombs. With such a fast-growing status, the Nabateans came into conflict with the Jewish world and the Romans, including a failed siege of Jerusalem by King Aretas II in 65 BC. The Romans under Pompey, who by that time had already controlled the Holy City, pushed the Nabateans back and managed to besiege Petra. This forced the Nabateans to pay tributes to Rome, effectively making it a client state to the latter, which allowed them to maintain a certain degree of independence.

For decades, both sides managed to maintain a stable relationship, until 59 BC when Malchus I became the king of the Nabateans. The new king decided to ally himself with the Parthian Empire, a major power in ancient Iran to the east of the Roman world. Together they waged military campaigns against the Romans which resulted in the former’s defeat. This worsened the relationship between Petra and Rome and prompted the latter to find new trade routes to bypass the Nabatean capital.

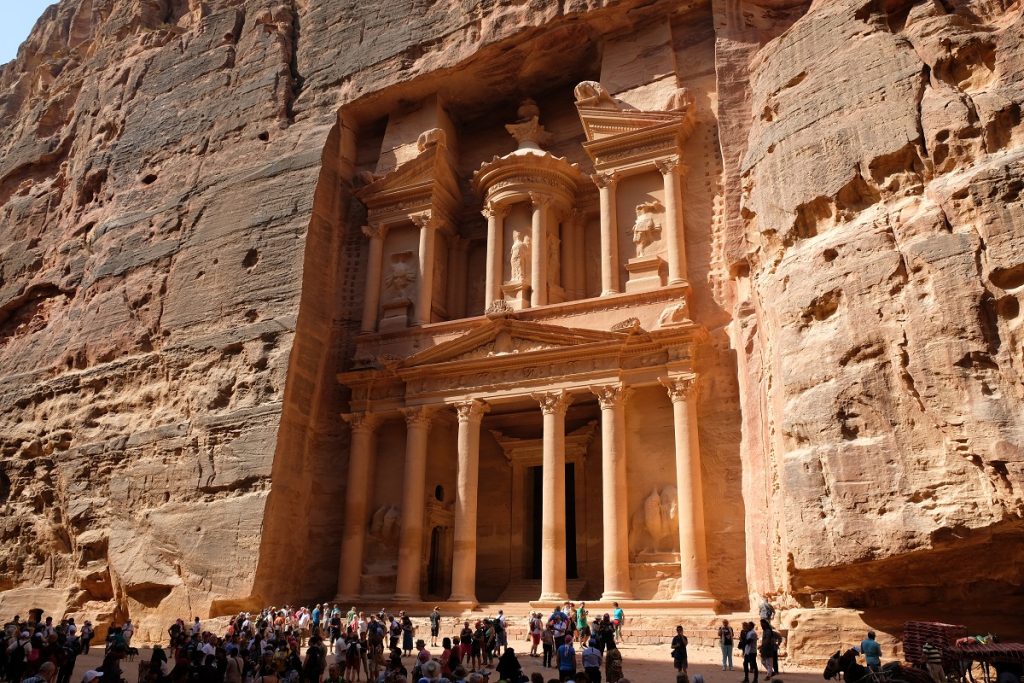

In 8 BC, a new Nabatean king ascended the throne and took the name Aretas IV. Under his reign, Petra experienced a new era of prosperity and peace which led to a “construction boom” of buildings on a monumental scale, most of them carved into the sandstone mountains that surrounded the city. Of all structures commissioned under his rule, the Treasury or Al Khazneh is the one we are most familiar with today – its iconic façade is emblematic not only of Petra, but also of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan itself.

Two thousand years later, James and I are walking down the gravel path that leads to the Siq, the main pathway to the ancient city of Petra. Although we both have the Treasury on our minds, it is hard not to be impressed with other structures we see along the way, including the Djin Blocks (three monolithic cubes created by cutting out a sandstone slope) as well as the Obelisk Tomb and the Bab Al Siq Triclinium that sits directly beneath the tomb. As we walk further, we come across a small bridge over a dried out river (purposefully left without water today for visitors’ safety) and arrive at the mouth of the Siq, a narrow passageway created by eons of wind and water erosion. On both sides of the gorge are niches which until 1896 still supported an arch. Unfortunately, after withstanding the elements for many centuries, that year it collapsed due to an earthquake.

While most visitors are busy taking photos of the Siq itself and the worn out niches along its walls, behind their back are vestiges of the Nabateans’ ingenuity in water management which helped propel them into great prosperity. Aqueducts were dug out on both walls of the Siq, upon which clay pipes were installed to channel water from surrounding springs into cisterns spread across Petra. The Petra Museum provides a wealth of information on this, and it blows my mind to realize just how advanced the Nabateans’ technology truly was.

The Siq snakes and curves for approximately 1.2 kilometers, narrowing at certain points into a three-meter wide fissure, rendering some parts of this entrance way to Petra dark even on a clear sunny day. This benefited the caravans in the past as these sections of the Siq made an ideal place as resting stations for the protection they provided from harsh weather conditions. The presence of merchant caravans is immortalized in carvings that adorn the gorge’s walls, although most of them have been badly damaged and eroded. Also located in the Siq are votive niches (inside which baetyli, or sacred stones, once resided) and stelae, suggesting this place’s sacredness for both locals and foreign merchants. We keep following where the Siq’s original stone paving – only rediscovered between 1997 and 1998 underneath layers of debris and sand that had accumulated over centuries – leads us. Horses and horse-drawn carriages dash past us and other tourists, through large openings where we can see the sky and tight gaps between the Siq’s walls that are barely large enough for those carts. And finally, there it is. A thin line of light at the end of the ancient pathway, revealing a sight I will never forget.

A few meters in front of us, at the very end of a narrow dark section of the Siq, lies that ancient structure now emblematic of Jordan itself: the Treasury or Al Khazneh. Even from this angle, it already looks impressive. But to truly marvel at the grandeur of this spectacular monument, one needs to complete his or her walk on the Siq and join hundreds of other tourists by stepping out into a wide natural courtyard. We all look up to the 40-meter high façade of this relatively well-preserved masterpiece of the Nabateans, admiring its fine architectural details as well as sculpted figures that were damaged centuries after its completion.

Believed to have served as the tomb of Aretas IV, the Treasury was built in the first century AD and constructed on top of even older funerary chambers. Its façade is a telltale sign of the cosmopolitan nature of the Nabateans, who took elements from different cultures to adorn both levels of the structure. At the center of the upper level is the Egyptian goddess Isis, flanked by a pair of Victories or Nikes and also a pair of Amazons (both sets inspired by the Greco-Roman world). On the lower level, guarding the entrance to the Great Hall, are Castor and Pollux, twin half-brothers in Greek and Roman mythology. The Nabateans’ indigenous architectural style is found atop the split pediment on the upper level in the form of double eagles. These ornate sculptures, however, were vandalized by Christian and Muslim iconoclasts many centuries later.

In Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, the Treasury is depicted as the true resting place of the Holy Grail. However, in reality the monument holds empty chambers which could once be accessed by tourists but are now off-limits to prevent damage to the sandstone due to touching, leaning, rubbing and an increase in humidity. James and I obsessively try to capture the icon from multiple angles, and before we know it we’ve already taken hundreds of shots of the Treasury. After all, it is a dream come true for both of us to see this ancient wonder with our own eyes.

To our right hand side as we stand facing the Treasury, the pathway continues. It takes us through the Street of Façades, named after the multiple tombs that were carved out of the red sandstone on both sides of the road, past even more burial places with Assyrian crow-steps sculpted above each entrance, and onto a massive Roman theater. This venue of artistic performances was dug out of the slope of a hill amid a series of cave-dwellings overlooking the main street below. I can only imagine the magnificence of Petra during its heyday.

We walk further on, and not long afterward we arrive at a sizable plain – on which the urban center of Petra had been constructed – with towering mountains guarding its west and east sides. If you have watched the 1999 Hollywood blockbuster movie The Mummy and its sequel The Mummy Returns, you must know about Hamunaptra, a fictional Egyptian city which stays hidden from plain sight most of the time. For some reason, the soundtrack that accompanies the scenes where Hamunaptra is revealed to the movies’ protagonists immediately plays in my head as I lay my eyes on the ruins that are spread out all across this plain. There are only a few places I’ve been to that left such a deep impression on me, and Petra is near the top of that list. Its sheer size is unfathomable given the harsh conditions of its geography, and everything about the place blows me away again and again as I take further steps into the center of this ancient city.