Petra has been amazing so far, and the Treasury is even more impressive in person even though I have seen countless pictures of this famous ancient monument prior to the trip. But James and I know there’s more than just this magnificent structure – believed to be the mausoleum of King Aretas IV – in Petra, so we follow the pathway through the Street of Façades toward the city’s massive Roman theater, situated right after a series of burial places of the Nabateans, carved out of red sandstone with Assyrian crow-steps decorating the entrance of each and every one of them. To my right, perched high above the hill is a particularly imposing tomb which was built in the first century AD. It was dedicated to Uneishu, the minister of Queen Shaquilat, wife of Aretas IV and mother of Rabbel II – Petra’s last king during whose childhood the queen reigned for six years.

Petra’s golden age of monument-building in fact occurred when Aretas IV was the king, under whom the Nabatean civilization was at its peak. After walking past the large theater, James and I arrive at the beginning of Petra’s urban center, a plain upon which the city’s most important temples were constructed. But before we go any further, a row of edifices to our right steals our attention.

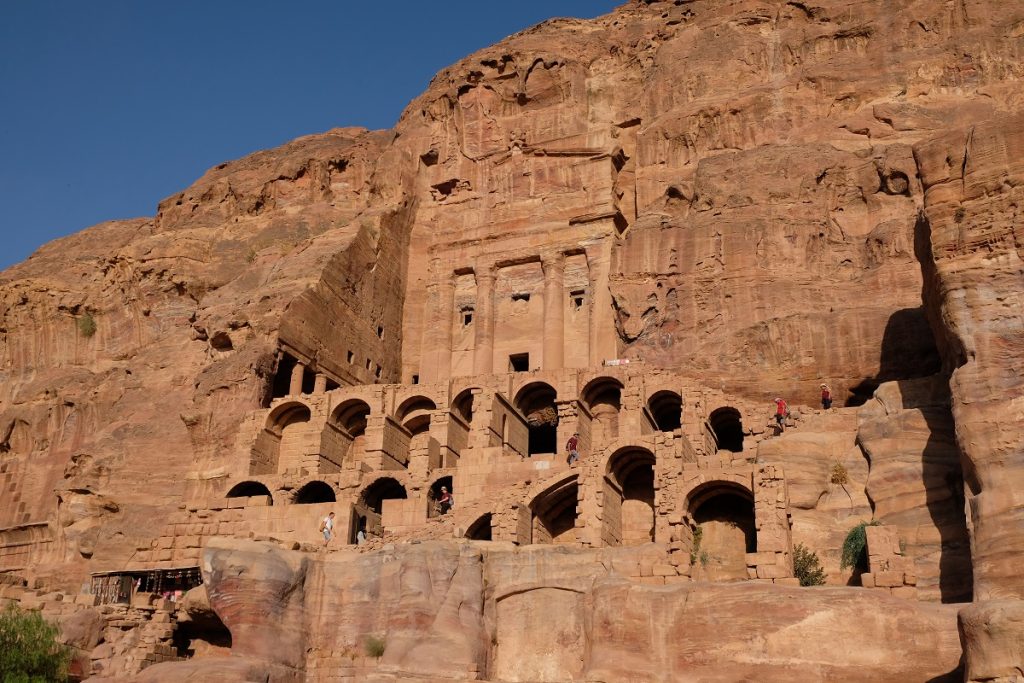

A series of highly ornate structures, all carved out of the rock face of Jabal al-Khubtha – one of the many jabals (mountains in Arabic) in Petra – shine brightly under the sun. Their reddish hue highlights the architectural elements – columns, pediment and other decorative details – of each monument, creating a stark contrast to the rugged landscape around them. These are the Royal Tombs, a collection of mausoleums built in different styles that are a testament to the cosmopolitan nature of the Nabatean people. We walk closer to the first one to the right. Called the Urn Tomb, after the acroterion (an ornament placed on a flat pedestal and mounted at the apex or corner of the pediment of a building in the Greek classical style) which resembles an urn, it was built on a substructure with multiple arches, making this particular tomb stand the tallest among the others.

We climb toward the entrance of the Urn Tomb and find ourselves at a courtyard. On our left-hand side is a portico adorned with Doric columns, while on the right-hand side is a souvenir stall attended by a middle-aged Bedouin man that occupies what is now a columnless niche. In front of us is the main structure’s façade. Although its bas-reliefs have been badly eroded, its columns and other decorative elements still exude a sense of grandeur. Once we walk through the entrance way, however, we find an austere large chamber with a few small niches. Despite the lack of ornamentation, the unplastered walls actually look stunningly beautiful, thanks to the natural patterns of the stone.

A more exquisite example of this polychromatic veining can be seen on a smaller tomb to the left of the Urn Tomb. Known as the Silk Tomb, this structure displays bands of color on its façade, from pink to salmon, white, blue, ochre and saffron yellow. This spectrum gives the otherwise modest tomb its ‘silky’ appearance. Adjacent to the Silk Tomb is another massive structure called the Corinthian Tomb, a name given by 19th-century Europeans due to its Nabatean horn capitals which were mistakenly identified as those of the Corinthian order. These very explorers were also the ones who labelled this tomb “a bad imitation” of the Treasury, although if one looks closely today, the two certainly have their own distinctive features. Directly next to the Corinthian Tomb is another large and equally-eroded mausoleum called the Palace Tomb, a name attributed to its resemblance to large Greek palaces.

All the four tombs bear no inscriptions which could suggest for whom they were built. However, it is generally accepted that they were all constructed in the first century AD, a period of time when the Nabateans were ruled by Aretas IV, followed by his direct successor Malchus II. A little further down in the valley, away from the Royal Tombs, is a lonely tomb which is also the only such structure in Petra that can be dated with relative accuracy. An inscription carved on its lower entablature mentions that the son of Sextius Florentinus – a legate of Emperor Hadrian and Proprietor of the Province of Arabia between 126 and 129/130 AD – dedicated this tomb as the resting place of his father. It is further confirmed by other sources that the Roman Governor did spend the last years of his life in Petra, probably out of his love for the city.

The Tomb of Uneishu

A closer look at this precariously-located tomb

The monumental façade of the Urn Tomb

The portico on the left-hand side of the courtyard at the Urn Tomb

However, Petra is not all tombs and mortuary edifices. Following the main road that connects the Treasury and the Roman theater westward, we arrive at a colonnaded street that was the urban center of the Nabatean capital. Along this Decumanus Maximus (the main east-west road) – which runs parallel to a now-dried watercourse for almost 300 meters – all sorts of buildings were constructed, from the city’s main temples to markets and baths. Most of them are now in ruins, although in the case of the Temple of the Winged Lion you can get an idea of how it once might have looked. Situated on a small hill on the northern side of the decumanus, what remains of the structure of this place of worship – which was named after the decorations found on some of its capitals – are its foundations. Two thousand years ago, however, when seen from the colonnaded street below, the temple must have been quite a sight. Today, visitors can look through a transparent display panel at the decumanus which superimposes an image of the temple’s reconstructed original appearance on what’s left of it.

Directly across it lies another, even bigger sanctuary that is currently the largest freestanding building that has been excavated in the ancient city. Called the Great Temple, it consists of a propylaeum (monumental gateway), a Lower and an Upper Temenos (sacred enclosures), both connected by stairways. The Nabatean-style capitals and architectural elements of this temple suggest that it was built in the first century AD during the peak of the Nabatean construction boom. We explore the empty corners of this impressive structure, enter one chamber after another, and at one point are separated from each other, before finally meeting again at a small theater at the heart of the temple compound. Probably this was how priests reached this sanctum in the past; they might have entered the temple from different entrance ways, but eventually gathered at the most sacred part of the whole complex. We walk back to the Lower Temenos, and marvel at the large round columns – some of them collapsed due to past earthquakes – of the porticoes from which we can see a steady stream of tourists below. Many seem oblivious to the existence of this building where we’re standing.

We go down the propylaeum, and join other visitors walking toward the Temenos Gate which marks the very end of the colonnaded street and served as the gate to a consecrated, open-air space where ceremonies to worship the deities were once held behind its long-lost big wooden doors. The gate also suffered from heavy damage due to earthquakes that rattled this ancient city, and today some of its decorative elements are kept safe in the Petra Museum.

Walking past the imposing gate, we are greeted by another monument with the towering Al Habis rock as its dramatic backdrop. Known as the Qasr al-Bint (short for the Qasr al-Bint Fir’aun, or the “Palace of Pharaoh’s Daughter”), after local Bedouin folklore about the origin of the building, this temple might have been constructed in the early first century AD on top of the remains of an older structure. Dedicated to the pre-Islamic Arab deities of Dushara/Dusares (often associated with Zeus) and Al-Uzza (a local equivalent of Aphrodite), the Qasr al-Bint is unique in Petra for the fact that it is among the very few structures in the ancient city that withstood multiple earthquakes that razed other buildings around it. This is believed to have been attributed to the use of wooden string courses around its structure that helped absorb the energy from the ground vibration. These, and other wooden parts of the temple, have been identified as Lebanese Cedar from the same species of ancient trees that we saw in the snowy mountains of Lebanon months earlier.

Restoration work is still undergoing at Qasr al-Bint, however, so we have to keep walking until we reach a crossroads. One of the pathways that branch out from here will lead us to a site where another monumental structure is supposedly located at the end of the trail. Years before I even planned to go to Jordan, I had learned about the Monastery (Ad Deir), one of the most iconic landmarks of Petra. The blog posts I read about it all mention that it takes a little more effort to visit this site as opposed to the easy-to-reach Treasury, which is the single structure that is included in every itinerary, from that of rushed-around tour groups to those planned by the most seasoned travelers. A few months before our departure to Jordan, an Indonesian travel blogger shared her experience in Petra and how her guide told her to hike up to the Monastery.

The original look of the Temple of the Winged Lion, superimposed onto its ruins